Summary:

Companies need a growth strategy that encompasses three related sets of decisions: how fast to grow, where to seek new sources of demand, and how to develop the financial, human, and organizational capabilities needed to grow. This article offers a framework for examining the critical interdependencies of those decisions in the context of a company’s overall business strategy, its capabilities and culture, and external market dynamics.

Perhaps no issue attracts more senior leadership attention than growth does. And for good reason. Growth—in revenues and profits—is the yardstick by which we tend to measure the competitive fitness and health of companies and determine the quality and compensation of its management. Analysts, investors, and boards pepper CEOs about growth prospects to get insight into stock prices. Employees are attracted to faster-growing companies because they offer better opportunities for advancement, higher pay, and greater job security. Suppliers prefer faster-growing customers because working with them improves their own growth prospects. Given the choice, most companies and their stakeholders would choose faster growth over slower growth.

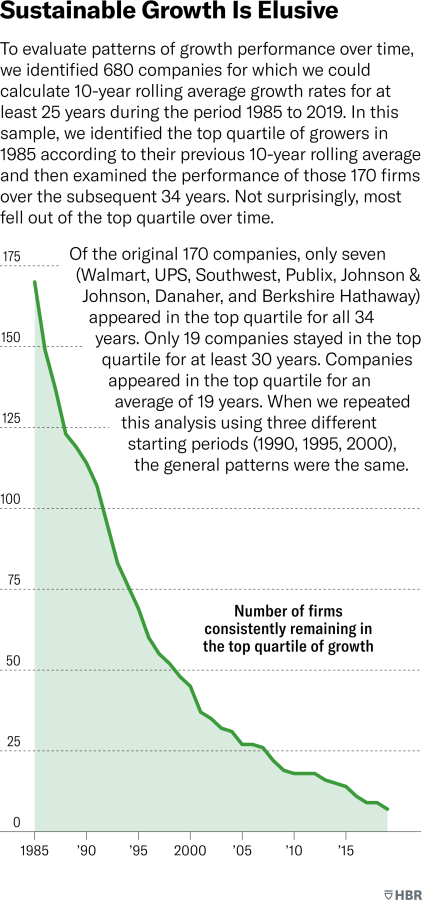

While sustained profitable growth is a nearly universal goal, it is an elusive one for many companies. Empirical research that I and others have conducted on the long-term patterns of growth in U.S. corporations suggests that when inflation is taken into account, most companies barely grow. For instance, in an analysis of 10,897 publicly held U.S. companies from 1976 to 2019, my research associate Catherine Piner and I found that firms in the top quartile grew at an inflation-adjusted average of 11.8% per year, but those in the lower three quartiles experienced little or no growth (0.3%, 0.03%, and -0.5%, respectively). And the majority of firms in the top quartile were unable to sustain superior growth performance for more than a few years. Although challenging to achieve, sustained profitable growth is not impossible, however. In our analysis, we found that only about 15% of the companies in the top growth quartile in 1985 were able to sustain their top-quartile performance for at least 30 years.

Over the past two decades, I have tried to understand why some companies are more effective at sustaining growth and what senior leaders can do to navigate the organizational challenges it poses. In addition to quantitative statistical analysis of large samples of U.S. companies over multiple decades, I have conducted case studies of more than 20 companies in a variety of industries, including semiconductors, software, health care, life sciences, restaurants, airlines, alcoholic beverages, luxury goods, apparel, hotels, and automobiles. I’ve also gleaned additional insights from my experience consulting for (and serving on the boards of) companies ranging in size from start-ups to some of the world’s largest corporations.

I have found that while the usual explanations for slow or minimal growth—market forces and technological changes such as disruptive innovation—play a role, many companies’ growth problems are self-inflicted. Specifically, firms approach growth in a highly reactive, opportunistic manner. When market demand is booming, they go on hiring binges, throw resources at developing new capacity, and build out organizational infrastructure without thinking through the implications—for example, whether their operating systems and processes can scale, how rapid growth might affect corporate culture, whether they can attract the human capital necessary to deliver that growth, and what would happen if demand slows. In the process of chasing growth, companies can easily destroy the things that made them successful in the first place, such as their capacity for innovation, their agility, their great customer service, or their unique cultures. When demand slows, pressures to maintain historical growth rates can lead to quick-fix solutions such as costly acquisitions or drastic cuts in R&D, other capabilities, and training. The damage caused by these moves only exacerbates the growth problems.

Sustaining profitable growth requires a delicate balance between the pursuit of market opportunities (demand) and the creation of the capabilities and capacity needed to exploit those opportunities (supply). To proactively manage that balance, companies need a growth strategy that explicitly addresses three interrelated decisions: how fast to grow (the target rate of growth); where to seek new sources of demand (the direction of growth); and how to amass the financial, human, and organizational resources needed to grow (the method of growth).

Each of those decisions involves trade-offs that must be considered in concert with a company’s overall business strategy, its capabilities and culture, and external market dynamics. (See the sidebar “The Perils of an Unintegrated Growth Strategy.”) My rate-direction-method (RDM) framework highlights the critical interdependencies between decisions that are all too often made separately. Using the framework to illuminate the trade-offs, companies can create a balanced growth strategy.

Rate: What Is the Right Pace of Growth?

The answer to this question seems obvious: as fast as possible. But taking a strategic perspective means that companies choose a target growth rate that reflects their capacity to effectively exploit opportunities. Growth is a strategic choice with implications for a company’s operating processes, financing, human resource strategy, organizational design, business model, and culture.

In finance, the concept of a sustainable growth rate is well understood: It is the fastest a company can grow without having to sell equity or borrow. But talent, organizational know-how, operational capabilities, management systems, and even culture are also resources required to produce goods and services, and they, too, can become bottlenecks constraining growth. A competent CFO will keep a company from growing faster than its financial resources will allow. Unfortunately, CEOs and leaders of other functions often do not apply the same disciplined thinking to nonfinancial resources (which constitute the vast majority of a firm’s value). For example, rapidly growing companies may downplay gaps between what their staffing levels, management capabilities, and operating processes can deliver and what is required to meet demand, seeing them as transitory “growing pains.” This approach can trigger a vicious circle. Shortfalls in critical capabilities can lead to quality and other operating problems, which in turn become a drain on already-stretched resources. With no time to design and install systems adequate to handle the growth, companies often attempt to “catch up” through massive hiring and infrastructure spending and other stopgap measures. Worker burnout and attrition are not uncommon. These firms find themselves with a patchwork of suboptimal systems, an unwieldy infrastructure, an exhausted workforce, and a tarnished reputation in the market. And the so-called growing pains turn out to be not so temporary.

A case in point is Peloton. During the pandemic, it reacted to the surge in demand for its exercise bikes and treadmills with a furious effort to expand manufacturing capacity and distribution. The expansion pushed the company’s supply chain beyond its capabilities, which led to quality and customer service problems (including two recalls). The cooling of pandemic-fueled demand left the company with a bloated cost structure.

The right strategy for many firms may be saying no to faster growth—even if the opportunities are tempting in the short term. Pal’s Sudden Service, a quick-serve restaurant chain with 31 outlets in the southeastern United States that Francesca Gino, Bradley Staats, and I studied, is an example of a company that has taken an exceptionally disciplined approach to growth. Founded in 1956, Pal’s has eschewed the rapid expansion of outlets favored by many fast-food chains. Since 1985, when it opened its third outlet, it has added, on average, less than one new restaurant per year and it has never opened more than one restaurant in any year. Pal’s boasts one of the highest revenues per square foot in the industry: $2,500 versus $650 for the typical burger chain. In an industry where scale economies are critical, the chain’s excellent financial performance is surprising. A key ingredient to its success is its operating system, which is designed around lean manufacturing principles. Every process, from where to place the ketchup on a burger to how far to open a hot dog bun, has been carefully studied and specified. The company’s menu is limited to a few basic items such as hamburgers, hot dogs, sandwiches, fries, and milkshakes.

With such a profitable and rigorous operating model, and seemingly unlimited demand in the United States for its products, a massive and lucrative expansion would appear to make sense. Yet the chain’s leadership recognizes that a unique aspect of its model places a limit on how fast it can grow: its obsession with quality. Pal’s has an extremely low rate of order errors: one error per 3,600 orders versus one error per 15 orders for the industry. That level of quality not only allows Pal’s to save costs on food waste, which is critical in an industry with low margins, but it also enables the company to have one of the fastest throughput times in the industry. In a drive-through operation, order errors cause delays for every customer down the line. Pal’s is able to serve more customers at peak hours, and that translates directly into higher revenue.

But the emphasis on quality also requires significant investment in resources—in particular, for extensive training and building the right culture in the workforce. At Pal’s, workers are trained for weeks on each process and must pass a certification test before they can make products for customers. They must be recertified periodically to ensure that their skills are up to par. All Pal’s stores are managed by “owner-operators” (who are not actually owners but whose compensation is tied 100% to their individual store’s profits). Pal’s believes that these managers are critical to nurturing the culture of quality and to training and developing talent. All manager candidates are put through an extensive screening process, and selected candidates, regardless of their prior industry experience, attend the company’s leadership-development program. It normally takes candidates three years to be allowed to run their own store. The company’s growth strategy is dictated by the availability of store managers: When Pal’s has a candidate ready, it will open a new store.

Notice the difference between the Pal’s approach to growth and that of most other companies. Pal’s does not set a growth goal on the basis of market potential or target financial returns. Instead, it recognizes its critical bottleneck resource—in this case, store managers—and paces growth according to the rate at which it can develop them. This approach has almost certainly meant slower growth in number of stores and revenue, but it has been critical to maintaining the company’s unique operating model and its superior financial performance.

In my research, I’ve found that most companies think of growth potential in terms of “demand side” factors: external trends, market share, and other metrics such as total addressable market. These are important, of course, but they are only half the story. Supply-side constraints matter just as much: High demand potential does not translate into profitable growth unless an organization has or can develop the capabilities needed to meet that demand. So a strategic perspective on growth means analyzing the company’s sustainable growth rate (considering all resources, not just money) and then thinking through the trade-offs inherent in faster or slower growth. For instance, there may be excellent strategic reasons to grow more quickly (for example, a market where first-mover advantages or network effects are present), but that faster growth must be weighed against the potential harm it creates.

Direction of Growth: Scale, Scope, or Diversify?

Since demand ultimately fuels growth, selecting which market opportunities to pursue is a critical component of a company’s overall growth strategy. Some companies seek growth by scaling in their core market. Others broaden their scope into adjacent products and services. Still others diversify into a range of seemingly unrelated industries. Which strategies are most profitable over the long term has long been a topic of hot debate, and my research suggests there is no simple answer.

Let’s return to the analysis of nearly 11,000 companies from 1976 to 2019. Among the fastest long-term growers, some companies—such as Walmart, UPS, Southwest Airlines, and Publix—grew by scaling in their core markets, replicating their model in new geographic markets, or adding ancillary services closely aligned with their core service operations. Others—such as Danaher, Johnson & Johnson (for which I have provided consulting services in the past), and Berkshire Hathaway—took the opposite approach in pursuing diversification strategies.

How should companies decide which path to take in their pursuit of growth? It is tempting to think about such choices as simply a matter of identifying and exploiting immature, unsaturated markets with rapid overall growth potential. While market dynamics matter, there are other factors to consider. For example, from 1980 to 2019 the average compound annual growth rate of the domestic U.S. travel market (in terms of “revenue passenger miles,” or the number of miles traveled by paying passengers) was a modest 5.3%. Southwest Airlines, however, enjoyed a brisk average CAGR of 15.3%. It accomplished that by developing unique operating capabilities (such as fast turnaround of aircraft) that enabled it to efficiently provide point-to-point service on routes that traditional competitors either ignored or served only through inconvenient hub-and-spoke models.

I’ve found that even in higher-growth industries, the distribution of growth rates tends to be highly skewed, with a small set of firms accounting for the lion’s share of industry growth. Consider the semiconductor industry. From 2015 to 2020, the top 10 semiconductor companies grew at an average annual compound rate of 9.2%. However, excluding the two fastest growers during this time (Nvidia, with a CAGR of 27%, and Taiwan Semiconductor, with a CAGR of 12.3%), the average dropped to 6.5%. Nvidia’s rapid growth stems from its capabilities in the design of powerful graphics processing units, or GPUs. Those capabilities helped Nvidia capture a 61% market share in the fast-growing market for chips used to power machine-learning and other artificial intelligence applications; the next closest rival is Intel, with a 16% share. The AI chip market offers high growth potential only to companies with the R&D capabilities to compete there—for others, it is not a particularly attractive opportunity.

The basic question that companies must address is: In which markets do our capabilities and other unique resources (such as brand, customer relationships, reputation, and so on) provide us with a competitive advantage? A scale-focused strategy will tend to revolve around deep, market-specific capabilities. Think about pharmaceutical companies. The capabilities that enable them to grow are their scientific prowess in drug discovery, understanding of clinical development and regulatory approval processes, and access to payer networks. While incredibly valuable for scale-based growth in pharmaceutical products, none of those capabilities transfers readily to other industries (including medical devices and diagnostics, which have different regulatory paths and market-access dynamics).

Successful scope strategies, in contrast, require the development of broader, general-purpose capabilities and resources that can be leveraged across market segments and lines of business. In some industries, brand equity is the basis for scope expansion. Consider the potent role that brand has played in Nike’s explosive growth over the past several decades as it expanded from being a maker of running shoes to a powerhouse across the sports apparel and equipment industry. In other cases, broad technological assets and capabilities open doors to new businesses. While conducting research on diversification patterns across more than 28,000 companies from 1975 to 2004, my colleague Dominika Randle and I analyzed patterns of patent citations to understand the degree to which a company’s technological capabilities were broadly applicable across markets. Our analysis showed that the companies with the most general-purpose technological assets (those that could be applied across multiple industries) were the most likely to diversify.

Method of Growth: How to Grow?

All growth requires access to new resources: financial capital, people and talent, brand, distribution channels, and so on. But there are various ways companies can choose to obtain them. A classic choice leaders face is how much to focus on organic growth versus growth by acquisition. Companies must also make decisions about how to finance growth, whether to vertically integrate or outsource to or partner with other firms, and whether to franchise or build out company-owned operations.

Obtaining any growth-fueling resource—money, people, brand, access to capabilities, and so on—involves trade-offs. Building up resources organically can take time (and thus result in slower growth), but those internally developed resources can often be more precisely aligned and integrated with a company’s unique value proposition. Partnering and outsourcing might provide a faster route to growth, especially for younger companies trying to bring products to market, but it can mean ceding control of activities critical to the value proposition.

Method decisions are tightly connected to choices about the rate and direction of growth. Consider the case of Virgin Group, which my colleague Elena Corsi and I studied. The company’s growth strategy is to expand into new markets and industries where the Virgin brand can drive customer acquisition. The company’s leaders consider the Virgin brand—along with fresh approaches to providing high-quality customer service—to be the firm’s critical resource. In many ways, Virgin’s rate of growth depends on the rate at which the brand can be monetized in new markets.

The privately owned Virgin Group has increasingly used licensing of its brand to drive growth. To raise the capital needed for acquisitions to enter new markets, Virgin divests existing businesses. In such cases, it generally strikes a licensing agreement with the acquirer for the right to use the Virgin brand. As a result of its aggressive use of licensing, Virgin Group’s most valuable asset, the Virgin brand, is increasingly under the control of organizations of which it is not a majority owner and over which it can exercise only limited control. This creates risks to the brand, even with vigilant monitoring and strict contractual clauses. While disputes between Virgin and its licensees are rare, they have happened. Looking at Virgin’s growth strategy through the rate-direction-method lens helps us understand the trade-offs the company has made. The licensing-driven method of growth enables broader diversification and faster growth, but it creates brand equity risks. A lower-risk approach would be to use less licensing (for instance, let the Virgin brand be used only in companies in which Virgin Group owns a majority share), but this would most likely mean less diversification and less growth.

What Makes a Great Growth Strategist

As companies grapple with the central question of how fast to grow, they’ll need leaders who understand the key decisions to be made and their inherent trade-offs. Good growth strategists are keenly aware of the nonfinancial constraints—such as systems, processes, human capital, and culture—on their company’s sustainable growth rate. They know that growing faster than capabilities dictate is possible in the short term but that doing so over the long term can cause lasting damage to reputation and culture. Good growth strategists do not fall into the trap of thinking they can grow fast now and fix things later. They recognize that more-measured growth over a sustained period will lead to much better financial results than explosive growth for a short period of time.

Great growth strategists, however, go beyond avoiding traps and accepting trade-offs. They proactively look for ways to augment the resources that constrain short-term growth and focus on the continuous accumulation of new resources and capabilities that open options for future growth, either through scaling in core markets or through entry into other markets. They see investments in training, processes, systems, technology, and culture as means to break growth bottlenecks and raise a company’s sustainable growth rate. They are comfortable with leading organizational change. Finally, they are obsessed with human capital. They recognize that among the many resources shaping a company’s growth potential, the quality, talent, and mindset of its people are the most important. Great growth strategists realize that sustained profitable growth is never going to be easy, but without the right human capital, it will be impossible.

Sidebar. The Perils of an Unintegrated Growth Strategy

B.good, a quick-serve restaurant founded in 2004, offers a cautionary tale about the need to make rate, direction, and method choices in an integrated manner when crafting a growth strategy. As a case study by Francesca Gino, Paul Green Jr., and Bradley Staats reveals, B.good has an innovative value proposition: Unlike most companies in the industry, B.good makes its burgers and other fast-food offerings using fresh, local ingredients. In addition, it cultivates a “family” culture for employees and customers: The founders got to know many employees and often reached out to them on special occasions or in difficult circumstances. Frontline employees were encouraged to greet customers by name and recommend members of their own families for jobs at the company.

B.good’s value proposition and its focus on culture created challenges operationally and organizationally. The focus on “fresh and local” and the unique cultural model made franchising—which requires more standardization and less corporate control over human resource decisions—and geographic expansion more difficult.

For the first eight years of B.good’s existence, it pursued a growth strategy compatible with its constraints: It opened only eight restaurants, all in the immediate Boston area and all completely company-owned. It had a cohesive growth strategy aligned with its core value proposition.

But then the company changed its growth strategy. It began to add outlets very quickly, a rate decision. By 2019, it operated 69 stores across the Northeast, South, Midwest, and Canada—a direction decision. And to finance growth, it began to sell franchises, a method choice; by 2019, 20% of its outlets were franchised.

In the aftermath of this change in strategy, the company struggled. Every time it expanded into a new geography, it needed to develop a new supplier base to fulfill its fresh and local promise. And every franchise selection required a time-consuming process to make sure the franchisee shared the founders’ philosophy. The company’s leaders should have realized that they faced a strategic choice: Either align its growth strategy with its core value proposition—which would have meant slower growth, less-aggressive geographic expansion, and less franchising—or change its value proposition and culture to enable faster growth, broader geographic expansion, and more franchising. They tried to have it both ways, and it didn’t work. As of 2023, the company was down to just 13 outlets, 11 of which were in metropolitan Boston and one each in Maine and New Hampshire.

Copyright 2024 Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation. Distributed by The New York Times Syndicate.

Topics

Strategic Perspective

Action Orientation

Systems Awareness

Related

How to Stand Out to C‑Suite RecruitersLessons Learned from the Restaurant Industry: What Outstanding Waiters and Waitresses Can Teach the Medical ProfessionMarketing at the Speed of CultureRecommended Reading

Strategy and Innovation

How to Stand Out to C‑Suite Recruiters

Strategy and Innovation

Lessons Learned from the Restaurant Industry: What Outstanding Waiters and Waitresses Can Teach the Medical Profession

Strategy and Innovation

Marketing at the Speed of Culture

Problem Solving

How to Make a Seemingly Impossible Leadership Decision

Problem Solving

Redefining Physician Leadership: A Comparative Review of Traditional and Emerging Competencies and Domains

Problem Solving

Bring Your Extended Leadership Team into Strategy Decisions