At first glance, the Hastings Center essay title seemed a bit humorous to me: “Smuggled Doughnuts and Forbidden Fried Chicken: Addressing Tensions Around Family and Food Restrictions in Hospitals.”(1) But then the article itself piqued my curiosity with “Family members often bring favorite foods to hospitalized loved ones, but when this food violates a patient’s dietary plan, tension and distrust can erupt between healthcare professionals and families.” It turns out there are several levels of ethical issues related to food in hospitals I had not previously considered.

My thoughts quickly tracked back to my trauma surgery background where our team often had to manage those smuggling food, drink, alcohol, and street drugs into patients’ rooms. We usually were able to de-escalate the situations with our “voice-of-authority” as caregivers, but occasionally we needed to bring in hospital security as well. And on occasion, I did walk around with a sore body part from being hit by patients as we “discussed” the importance of their being compliant with our treatment plans.

Most of us are aware of increasing workplace violence in patient care settings and even the resulting caregiver deaths. The frequency of injuries from workplace violence in healthcare has risen almost every year since 2011, reaching 10.4 per 10,000 full-time workers in 2018, up 62% from 6.4 per 10,000 in 2011, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.(2)

According to a recent Axios report,(3) in 2020, the most recent year for which statistics are available, about three in four nonfatal workplace violence injuries involved workers in healthcare and social work. Healthcare workers now suffer higher rates of violence than all other social support professions, including police.

There seems to be a paradox at play here, however. Although there has been a slight erosion in these numbers since the main thrust of the COVID pandemic, the healthcare professions are the most trusted by the public (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Most- and Least-Trusted Professions.

Perhaps trust is the core issue underlying workplace violence?

In this regard, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation, in a recently launched initiative focused entirely on trust, Building Trust,(4) stated, “Trust is a key element of our mission to advance medical professionalism to improve healthcare. It lies at the very heart of many commitments of the Physician Charter,(5) such as maintaining trust by managing conflicts of interest, being honest with patients, and preserving patient confidentiality.” Similarly, according to the ABIM Foundation, although there is variation across ethnic groups, 78% of people continue to trust their primary doctor.

THE TRUST EQUATION

Concerning leadership, numerous articles from across industry detail how the attribute of trust and being trustworthy is the dominant characteristic expected of leaders, ranging from juniors in an organization to peers in a C-suite.

Charles Green is credited with introducing the concept of a trust equation (see below).(6) Based on four components, its simplicity provides context for how physicians might better approach their own efforts in trusting environments or in those with perceived lack thereof.

As the equation implies, trust and trustworthiness are predicated on these components:

Credibility — Our knowledge base and the words we speak, or the expertise we are able to demonstrate. High credibility is good.

Reliability — Our actions and our dependability to do things when we say we will and with high quality. High reliability is good.

Intimacy — How secure we feel entrusting someone with personal information and sharing our vulnerabilities with another person. High capability for intimacy is good.

Self-Orientation — Our own self-interests, as opposed to our interest in others and our ability to focus on others. High self-interest is poor.

Green takes it a step further by developing and validating the Trust Quotient (TQ).(7) Answers to five questions related to each of the four components generate a total score that indicates how to make changes if needed or wanted. Apparently, women rate themselves higher than men as being more trustworthy (better with intimacy), but everyone believes themselves to be more trustworthy as they age (exhibiting less self-interest).

Physicians are inherently altruistic and idealistic, with a focus on helping others. These attributes will likely allow most physicians to score high on the numerator components of the equation. If there is a potential for a physician to score a lower TQ, it is likely to come from the denominator of self-interest, which would be understandable, given the demands of medical training and practice environments with the complex financial systems and high-demand reporting requirements.

Frustration and burnout will lead to increased self-interest and orientation simply because we physicians are all humans trying to cope with increasingly intense pressures as we deliver patient-centered care within an evolving value-based care delivery system.

Although the patient-physician relationship is under duress, patients generally still trust their physicians.

Patients and physicians, however, trust the delivery system less than they did pre-pandemic. As physician leaders, we can take advantage of the current state of misgivings and perceived lack of trust among and by healthcare providers. Demonstrating trustworthiness directly and facilitating the capabilities for others to be trusting of physicians will encourage others in the industry to more easily follow by example.

Physicians who are held in high regard within the industry, within hospitals, and within communities can overcome a difficult period in the healthcare industry by demonstrating how to create positive change from within.

For example, an October 3, 2023, NEJM Catalyst article by Luci Leykum, MD, MBA, MSc, “Reconceptualizing Primary Care: From Cost Center to Value Center,”(8) challenges the industry to not only continue shifting toward value-base care models, but also to rethink the basis for these models — i.e., building on relationships and trust:

“Effective relationships are grounded in knowing the patient as a whole person... Implementing a relationship-based model requires operational changes beyond just the requirements of patient-centered medical homes and concepts such as putting patients at the forefront, knowing your patients, care management and coordination, and access and continuity.”

Leykum eloquently goes on to state: “We must redefine primary care value in a way that goes beyond cost reduction and revenue maximization. We must combat clinician burnout and regain trust and find a sustainable path for health systems. Expense reduction and revenue maximization will reach their limits in diminishing returns... .”

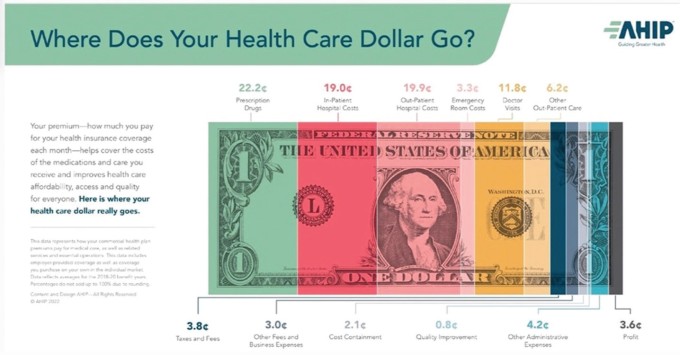

We all know there is plenty of money in the U.S. healthcare system — approaching $4.5 trillion/year and 20% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Physician visits are only about 12% of those dollars (see Figure 2). But physician leadership potentially represents an outsized opportunity to strongly influence the other 88% of how those dollars are distributed and spent. Our patients trust us, other healthcare providers trust us, and the non-clinical administrators and policymakers trust us. We must ensure ongoing trust by demonstrating trustworthiness and leadership as only physicians are able in healthcare.

Figure 2. Where Healthcare Dollars Go.

CREATING POSITIVE TRANSFORMATION

As physician leaders, we must embrace the complexities of our industry and the opportunities where our individual and collective energies can create the required positive transformation for our industry — a transformation highly predicated on the trust quotient that has been inherent in the patient-physician relationship for centuries. Let us all continue to maximize the opportunities before our profession. True patient-centered care and value-based care will evolve as a result.

Remember, leading and helping create significant positive change is our overall intent as physicians. AAPL focuses on maximizing the potential of physician-led, inter-professional leadership to create personal and organizational transformation that benefits patient outcomes, improves workforce wellness, and refines the delivery of healthcare internationally.

Through this AAPL community, we all can continue to seek deeper levels of professional and personal development, and to recognize ways we can each generate constructive influence at all levels. As physician leaders, let us become more engaged, stay engaged, and help others to become engaged. Exploring and creating the opportunities for broader levels of positive transformation in healthcare is within our reach — individually and collectively.

References

Dean MA, Guidry-Grimes L. Smuggled Doughnuts and Forbidden Fried Chicken: Addressing Tensions Around Family and Food Restrictions in Hospitals. The Hastings Center Report. August 7, 2023. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hast.1496 .

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Workplace Violence in Healthcare, 2018. Fact Sheet. April 2020. https://www.bls.gov/iif/factsheets/workplace-violence-healthcare-2018.htm .

Reed T, Millman J. Hospitals and Clinics Are Now Among America’s Most Dangerous Workplaces. Axios. August 10, 2023. https://www.axios.com/2023/08/10/escalating-violence-americas-hospitals .

ABIM Foundation. Building Trust: Focusing on Trust to Improve Health Care. American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. https://abimfoundation.org/what-we-do/rebuilding-trust-in-health-care .

ABIM Foundation. Medical Professionalism in the New Millennium: A Physician Charter. American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. Philadelphia, PA: ABIM Foundation; 2002. https://abimfoundation.org/what-we-do/physician-charter .

Green CH. My Trust Story. Trusted Advisor Associates LLC. https://trustedadvisor.com/consultants/charles-h-green .

Green CH. The Trust Quotient and the Science Behind It. Trusted Advisor Associates LLC. https://trustedadvisor.com/why-trust-matters/understanding-trust/the-trust-quotient-and-the-science-behind-it .

Leykum LK. Reconceptualizing Primary Care: From Cost Center to Value Center. NEJM Catalyst. October 3, 2023. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.22.0462 . https://doi.org/10.55834/plj.4290978704