Patient satisfaction surveys have gained importance since 2017, when they were adopted by Medicare as one criterion for judging physician quality. Medicare’s Merit based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) program is a pay-for-value model that replaced the traditional fee-for-service model. MIPS uses a composite score to determine physician reimbursement, with the goal of lowering costs and rewarding higher-performing physicians at the expense of underperforming physicians.(1) Physician quality accounts for 30% of the total composite score used in MIPS.(1) Patient satisfaction surveys can be used when determining the physician quality score, and, therefore, these surveys can adjust physician reimbursement. Lastly, all physicians’ yearly MIPS scores are retained and will be made publicly available by CMS.(1,2)

Even prior to the MIPS program, patient satisfaction surveys have long been used by clinic and hospital administrators to assess patient satisfaction with their care, patient likeliness to promote their business, and patient satisfaction with overall business practices (e.g., scheduling appointments, billing processes). Patient satisfaction surveys also are required for accreditation purposes, and these survey scores are used in the benchmarking of healthcare organizations.(3)

Numerous studies have analyzed how patient satisfaction scores for the same physician can vary based on nonmodifiable patient demographics such as gender,(4–9) age,(4–9) race,(5–7,9–11) and insurance status.(5–9) If nonmodifiable patient demographics influence survey scoring, physician reimbursement could be affected by inherent demographics of their patient population, as in capitated payment models. Therefore, physicians, administrators, and payers have a rational and substantial interest in patient satisfaction scores being adequately calibrated in order to accurately reflect physician quality and good patient care.(12)

To our knowledge, this presented study is the first systemic review to date on the association between gender and patient satisfaction scores across different specialties, including urology.

Materials and Methods

A focused systemic literature search was performed on the U.S. National Library of Medicine database (PubMed) according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Mata-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. The predefined search terms “patient satisfaction” and “gender” were used to identify articles describing a relationship between patient satisfaction scores and gender. The inclusion criteria for the search were: (1) articles in English; (2) published in the period 2007 to the present; and (3) adult patients only. The exclusion criteria were: (1) articles not published in English; (2) pediatric (nonadult) cohort; and (3) no detailed data on gender and satisfaction scores provided. The effect sizes of individual studies were modeled as odds ratio. Fixed-effects modeling (also called common-effect modeling) was used to produce an overall summary estimate and its 95% confidence interval (CI) for outcome; our analysis also was computed I(2) (the percentage of variability in the effect sizes). Heterogeneity was considered present substantially if I(2) > 75% or moderately if I(2) > 50%.(13) Lastly, the presence of publication bias was investigated using a funnel plot and Egger’s regression test.(14)

Results

Figure 1 outlines the search strategy and study selection done according to the PRISMA guidelines.(15) There were 360 studies identified for the period 2007 to present, and 13 non-English papers were excluded. One individual screened the remaining papers by title, which resulted in 212 papers being removed for either not mentioning patient satisfaction or not focusing on nonmodifiable patient demographics. Further papers were excluded for the following reasons:

No demographic correlation or the wrong demographic focus (n=9);

Patient satisfaction unrelated to physicians (n=5);

Pediatric patient population (n=2);

Only evaluating patient satisfaction survey design (n=2);

Incompatible statistics (n=1); and

Phone surveys (n=1).

Twenty-five papers were reviewed in their entirety. Twenty-one additional papers were included in this systemic review, discovered as follows:

As citation in previously identified papers and complying with the study’s inclusion criteria (n=18);

From an additional PubMed search using only one of the terms “patient satisfaction” or “gender” (n=2); and

From an intra-institutional study (n=1).

Note: Two studies reported data for both inpatient and outpatient populations, and only outpatient results were included in our analysis. The total number of papers included in this systemic review was 26.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

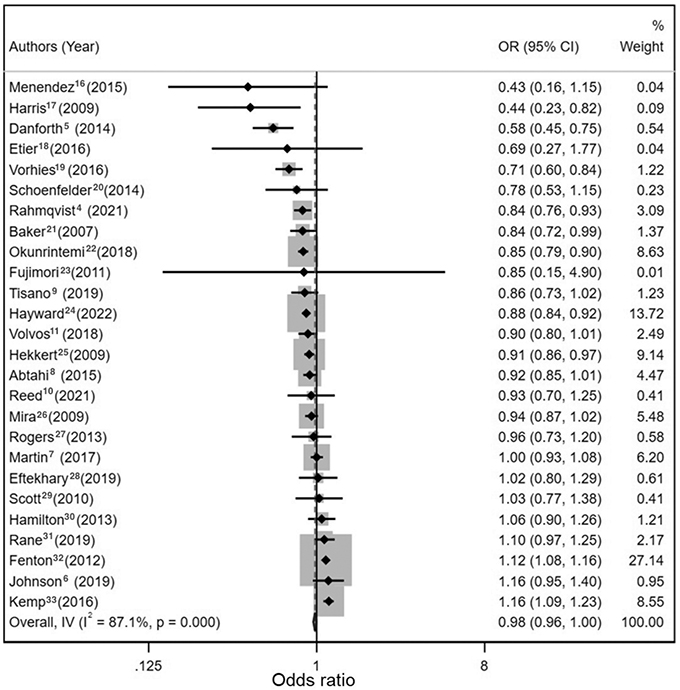

Table 1 and Figure 2 present the pertinent findings of the 26 included studies. The sample sizes of each cohort ranged from 69 to 51,946 patients, resulting in a total of 216,363 patients. Two studies were in urology; the other representative studies were in cardiology and other surgical specialties, including otolaryngology, hand surgery, neurosurgery, general surgery, and orthopedic surgery. The analysis revealed that women were statistically less likely than men to provide higher patient satisfaction scores, with an odds ratio of 0.98 (95% CI, 0.961-0.997; I(2) = 87.1%). This odds ratio of 0.98 is close to 1, therefore indicating that gender and patient satisfaction scores are unlikely to be associated. Figure 3 shows that no publication bias was found in the funnel plot and the Egger’s test (p =.053).

Figure 2. Forest plot showing a visual representation of odds ratio and confidence interval for each included study. The larger the odds ratio, the more likely the shown association is true. The impact of each study on the overall odds ratio is shown in the “% weight” column.

Figure 3. A funnel plot was created by plotting each study’s standard error against its odds ratio. This so-called Egger’s test would reveal any publication bias inherent in the included studies if the plot was asymmetric.

Discussion

When participating in the CMS program, each MIPS participant selects from over 300 different parameters to calculate the quality portion of their overall score, with patient satisfaction surveys being one option. Currently, there is an increasing movement among physicians to reform patient satisfaction surveys, because their importance can contribute to physician burnout, further negatively impacting empathy and communication skills.(12) This could be a vicious cycle for physicians, leading to a steady decline in satisfaction scores.(34) On the other hand, several studies have reported contradictory satisfaction scores of the same physicians due to nonmodifiable patient demographics such as gender,(4–9) age,(4–9) race,(5–7,9–11) and insurance status.(5–9) Additionally, patient satisfaction scores can be reported inaccurately by consulting firms and internal business practices that help institutions to raise their overall patient satisfaction scores without any improvement in quality of medical care or outcome, which essentially leads to “gaming the system.”(12) For example, a clinic or hospital could avoid sending out their patient satisfaction surveys on days where software malfunctions occurred, on days where appointments were canceled due to bad weather conditions, or during construction or remodeling of patient parking areas. Apparently accurate and fair assessment of patient satisfaction scores is difficult and may have significant subjective flaws. Based on these experiences, some practices and institutions choose to include patient satisfaction scores in their MIPS calculation only if their scores are already high, leading to further “gaming of the MIPS scoring system.”(36) Even if practices do not choose to submit their patient satisfaction scores as part of their MIPS score calculation, most practices do use these scores for accreditation and internal feedback. Increasing overall scores is beneficial, therefore: a high patient satisfaction score can increase reimbursement rates from Medicare through the MIPS system, improve benchmarking against their peers, and improve executives’ assessment of overall performance. Consequently, it is crucial that these scores accurately reflect patient satisfaction and the quality of care delivered.

Fenton et al.(32) found that patient satisfaction scores did not persistently correlate with good patient outcomes. Kemp et al.(33) showed that patient safety indicators (PSIs), such as delirium, cardiac events, and other negative complications of inpatient care, are associated with a lower likelihood of providing high patient satisfaction scores, and suggested that additional metrics could be used to provide a more accurate reflection of clinical quality and outcome. Adding extra metrics to patient satisfaction scores, such as PSI, could help to ensure that a more accurate reflection of the quality of care is provided.

Many of the studies included in this systemic review have identified deviations in satisfaction scores caused by nonmodifiable patient characteristics. However, the findings of this systemic review support the hypothesis that patient satisfaction scores are not gender-dependent, and, therefore, surveys can be simplified. Gender does not have to be accounted for when adjusting overall patient satisfaction scores for a large practice. The data presented do not support any definitive evidence for a gender bias in patient satisfaction scores, which could otherwise lead to further gamification of survey results and physician reimbursement.

Some studies presented in this review revealed conflicting results, showing that in certain situations gender may influence patient satisfaction scores. Menendez et al.,(16) Harris et al.,(17) and Danforth et al.,(5) reported that women were half as likely as men to have higher patient satisfaction scores. These results could have been influenced by their small sample sizes or by their very specific patient populations, such as related to orthopedic trauma (e.g., obtained in motor vehicle accident in the Harris study), or complex hand surgery (as presented in the Menendez study). When performing a multilevel analysis of patient satisfaction score variability, Hekkert et al.,(25) found that departmental and hospital level factors played a smaller role in determining patient satisfaction than inherent patient demographics. This demonstrates that patient satisfaction scores might be influenced by specific situations, rather than contact with a specific department in the hospital. Although 19 out of the 26 papers found women to be less likely than men to report higher patient satisfaction scores, this was not the overall finding of this review study, as illustrated in the Forest plot (Figure 2).

Patients who are more polarized in their satisfaction or dissatisfaction than the patient population as a whole may be more likely to respond to surveys.

We are aware of limitations associated with this systemic review. First, many studies have low survey response rates, which is a significant problem for patient satisfaction studies in general.(35) Additionally, patients who are more polarized in their satisfaction or dissatisfaction than the patient population as a whole may be more likely to respond to surveys. Furthermore, showing gender differences stratified by patient age would be interesting; however, the data presented did not provide adequate information to answer this question. Lastly, in many studies the data were collected from a specific or distinct geographic location, which may not be representative for other regions or the country as a whole.

Despite these limitations and based on the overall or summarizing results across numerous specialties, including surgical subspecialties such as urology, women and men seem to have equal odds of being satisfied with their physician. This should reassure physicians and their clinics that satisfaction scores and associated reimbursement are not affected by the gender mix of their patient cohorts.

Conclusions

Although some studies report that women had slightly lower odds of submitting higher patient satisfaction scores than men, the overall summary estimate of the odds ratio in this systemic review was very close to 1, indicating that gender and patient satisfaction scores have an unlikely association. These findings should alleviate any concern that gender might affect patient satisfaction surveys, and therefore, physician reimbursement.

Acknowledgment. We thank Sun-Hee Kim, MSPH (Biostatistics), PhD (Molecular and Cellular Biology) for advice and support in statistical analysis of the presented data.

References

Merit Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS)—What is MIPS? MDinteractive. June 7, 2022. http://mdinteractive.com/MIPS . Accessed November 22, 2022.

Doctors and Clinicians Datasets. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. December 1, 2022. Updated November 17, 2022. https://data.cms.gov/provider-data/search?theme=Doctors+and+clinicians . Accessed December 1, 2022.

Section 2: Why Improve Patient Experience? Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. April, 2016. Updated February 2020. www.ahrq.gov/cahps/quality-improvement/improvement-guide/2-why-improve/index.html

Rahmqvist M, Bara AC. Patient characteristics and quality dimensions related to patient satisfaction [published correction appears in Int J Qual Health Care. 2021 Feb 5;33(1):]. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22(2):86-92. DOI:10.1093/intqhc/mzq009

Danforth RM, Pitt HA, Flanagan ME, Brewster BD, Brand EW, Frankel RM. Surgical inpatient satisfaction: what are the real drivers? Surgery. 2014;156:328-335. DOI:10.1016/j.surg.2014.04.029

Johnson BC, Vasquez-Montes D, Steinmetz L, et al. Association between nonmodifiable demographic factors and patient satisfaction scores in spine surgery clinics. Orthopedics. 2019;42(3):143-148. DOI:10.3928/01477447-20190424-05

Martin L, Presson AP, Zhang C, Ray D, Finlayson S, Glasgow R. Association between surgical patient satisfaction and nonmodifiable factors. J Surg Res. 2017;214:247-253. DOI:10.1016/j.jss.2017.03.029

Abtahi AM, Presson AP, Zhang C, Saltzman CL, Tyser AR. Association between orthopaedic outpatient satisfaction and non-modifiable patient factors. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:1041-1048. DOI:10.2106/JBJS.N.00950

Tisano BK, Nakonezny PA, Gross BS, Martinez JR, Wells JE. Depression and non-modifiable patient factors associated with patient satisfaction in an academic orthopaedic outpatient clinic: is it more than a provider issue?. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477:2653-2661. DOI:10.1097/CORR.0000000000000927

Reed NS, Boss EF, Lin FR, Oh ES, Willink A. Satisfaction with quality of health care among Medicare beneficiaries with functional hearing loss. Med Care. 2021;59(1):22-28. DOI:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001419

Vovos TJ, Ryan SP, Hong CS, et al. Predicting inpatient dissatisfaction following total joint arthroplasty: an analysis of 3,593 hospital consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems survey responses. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:824-833. DOI:10.1016/j.arth.2019.01.008

Richman BD, Schulman KA. Are patient satisfaction instruments harming both patients and physicians? [published online ahead of print, 2022 Nov 17]. JAMA. 2022;10.1001/jama.2022.21677. DOI:10.1001/jama.2022.21677

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539-1558. DOI:10.1002/sim.1186

Harbord RM, Egger M, Sterne JAC. A modified test for small-study effects in meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Statistics in Medicine. 2006;25:3443-3457. DOI:10.1002/sim.2380

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. Published 2021 Mar 29. DOI:10.1136/bmj.n71

Menendez ME, Chen NC, Mudgal CS, Jupiter JB, Ring D. Physician empathy as a driver of hand surgery patient satisfaction. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40:1860-5.e2. DOI:10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.06.105

Harris IA, Dao ATT, Young JM, Solomon MJ, Jalaludin BB. Predictors of patient and surgeon satisfaction after orthopaedic trauma. Injury. 2009;40:377-384. DOI:10.1016/j.injury.2008.08.039

Etier BE Jr, Orr SP, Antonetti J, Thomas SB, Theiss SM. Factors impacting Press Ganey patient satisfaction scores in orthopedic surgery spine clinic. Spine J. 2016;16:1285-1289. DOI:10.1016/j.spinee.2016.04.007

Vorhies JS, Weaver MJ, Bishop JA. Admission through the emergency department is an independent risk factor for lower satisfaction with physician performance among orthopaedic surgery patients: a multicenter study. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24:735-742. DOI:10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00084

Schoenfelder T, Schaal T, Klewer J, Kugler J. Patient satisfaction in urology: effects of hospital characteristics, demographic data and patients’ perceptions of received care. Urol J. 2014;11:1834-1840. Published 2014 Sep 6.

Baker PN, van der Meulen JH, Lewsey J, Gregg PJ; National Joint Registry for England and Wales. The role of pain and function in determining patient satisfaction after total knee replacement. Data from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:893-900. DOI:10.1302/0301-620X.89B7.19091

Okunrintemi V, Valero-Elizondo J, Patrick B, et al. Gender differences in patient-reported outcomes among adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(24):e010498. DOI:10.1161/JAHA.118.010498

Fujimori T, Iwasaki M, Okuda S, et al. Patient satisfaction with surgery for cervical myelopathy due to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;14:726-733. DOI:10.3171/2011.1.SPINE10649

Hayward D, Bui S, de Riese C, de Riese W. Association of age, gender, and health-insurance category as nonmodifiable parameters on patient satisfaction scores in an academic urology clinic. J Med Pract Manage. 2022;37(5):223-228.

Hekkert KD, Cihangir S, Kleefstra SM, van den Berg B, Kool RB. Patient satisfaction revisited: a multilevel approach. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(1):68-75. DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.016

Mira JJ, Tomás O, Virtudes-Pérez M, Nebot C, Rodríguez-Marín J. Predictors of patient satisfaction in surgery. Surgery. 2009;145:536-541. DOI:10.1016/j.surg.2009.01.012

Rogers F, Horst M, To T, et al. Factors associated with patient satisfaction scores for physician care in trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75(1):110-115. DOI:10.1097/TA.0b013e318298484f

Eftekhary N, Feng JE, Anoushiravani AA, Schwarzkopf R, Vigdorchik JM, Long WJ. Hospital consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems: do patient demographics affect outcomes in total knee arthroplasty?. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:1570-1574. DOI:10.1016/j.arth.2019.04.010

Scott CE, Howie CR, MacDonald D, Biant LC. Predicting dissatisfaction following total knee replacement: a prospective study of 1217 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:1253-1258. DOI:10.1302/0301-620X.92B9.24394

Hamilton DF, Lane JV, Gaston P, et al. What determines patient satisfaction with surgery? A prospective cohort study of 4709 patients following total joint replacement. BMJ Open. 2013;3(4):e002525. Published 2013 Apr 9. DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002525

Rane AA, Tyser AR, Kazmers NH. Evaluating the impact of wait time on orthopaedic outpatient satisfaction using the Press Ganey survey. JB JS Open Access. 2019;4(4):e0014. Published 2019 Oct 18. DOI:10.2106/JBJS.OA.19.00014

Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, Franks P. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:405-411. DOI:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1662

Kemp KA, Santana MJ, Southern DA, McCormack B, Quan H. Association of inpatient hospital experience with patient safety indicators: a cross-sectional, Canadian study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e011242. Published 2016 Jul 1. DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011242

Neumann M, Wirtz M, Bollschweiler E, et al. Determinants and patient-reported long-term outcomes of physician empathy in oncology: a structural equation modelling approach. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;69(1-3):63-75. DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2007.07.003

Hayward D, de Riese W, de Riese C. Potential bias of patient payer category on CG-CAHPS scores and its impact on physician reimbursement. Urology Practice. 2021;8(2):183-188. DOI:10.1097/upj.0000000000000195

Roberts ET, Song Z, Ding L, McWilliams JM. Changes in patient experiences and assessment of gaming among large clinician practices in precursors of the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(10):e213105. DOI:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.3105