Summary:

Private-equity-backed companies consistently deliver faster, more substantial gains than their public or family-owned peers, often transforming their performance within just a few years. Their playbook consists of six practices. Leaders in any sector can adopt them to accelerate growth, improve efficiency, and strengthen long-term performance.

Private equity (PE) firms have often been portrayed as corporate raiders—investors who snap up companies, pump up their numbers through cost cutting and financial engineering, sell them at huge profits, and move on. But that view is outdated. In recent decades some of the industry’s traditional tactics, such as asset carve-outs (selling off divisions or subsidiaries) and sale leasebacks (selling a company’s property and then leasing it from the new owner), have become so widespread that they no longer guarantee exceptional returns. So today’s most successful PE firms have found a more straightforward way to create surplus value: They’ve learned how to build better businesses faster.

Multiple academic studies have confirmed that PE-owned companies outperform their peers—not only by delivering better financial returns but also by making transformative operational improvements. On average the companies PE firms buy achieve productivity gains of 8% to 12% in the first two years after their acquisition—far outpacing the 2% to 4% gains that public companies typically see.

The conventional wisdom is that PE-backed firms operate in a unique environment because their ownership structure, governance, and incentives differ from those of most firms, and that for that reason, their techniques won’t work well in other contexts. Our research and experience suggest that’s not true. In fact, we believe that CEOs and executive teams in any kind of business should seek to understand and, where appropriate, adopt their methods.

In our research and through our collaborations with more than 120 CEOs participating in the Harvard Business School–McKinsey PE CEO Excellence leadership program, we have seen these practices drive superior performance. Many PE firms have applied them across hundreds of portfolio companies of various sizes and in various industries, proving that they can be used by many types of businesses. In this article we will highlight six of their most successful tactics.

[ 1 ] Conduct Full-Potential Due Diligence Continually

Before acquiring a company, PE investors rigorously define an investment thesis for it and set clear performance expectations. As part of that process, they create a financial model that outlines the “momentum case” (what’s likely to happen to the firm if there are no major changes or disruptions) and the “full potential” case (what’s possible if the firm makes bold moves).

Effective CEOs of PE-backed companies don’t stop there. They regularly revisit this analysis—often independently of their PE owners—to ask whether the business can go further. They examine their companies as if they were potential investors: What opportunities are being missed? What costs or risks are hiding in plain sight? Where is bold action needed?

All CEOs can similarly look at their businesses from the outside in, quantify the upside, and create a plan to lift their companies’ current trajectories. They can ask themselves—as the management thinker Peter Drucker once urged an executive to do—“If you weren’t already in this business, would you enter it today?” And if not, “What are you going to do about it?”

Many successful PE-owned companies form independent diligence teams of analytically rigorous individuals from across the business, sometimes complementing them with external consultants. The team members synthesize a new or updated full-potential thesis about why a prospective owner would invest in the business and the upside that could be delivered in a fixed time frame, typically two or three years. That requires systematically evaluating every critical business area and usually takes six to 10 weeks.

The diligence team analyzes all strategic, commercial, financial, and operational factors, including cost structure, capital expenditures, working capital, and overall risk. After identifying what needs improvement, the team determines precisely how to implement changes—mapping out necessary shifts in organizational structure, leadership, incentive schemes, and management systems.

Though most companies conduct regular strategy and business reviews, PE-backed firms implement them across the organization and much more deeply. The best CEOs of PE-owned companies have full-potential diligence done every two to three years, rather than only in response to major market shifts. Like the CEO, the diligence team adopts the fresh perspective of new investors—free from past habits, existing biases, and established orthodoxies—and commits to challenging prevailing assumptions, which forces a sharper, less sentimental look at legacy practices. And the outcome isn’t just a list of goals and insights; it’s a detailed, time-bound execution plan tied to measurable financial improvements, with clear accountability for delivering results.

A CEO of a PE-owned company recently told us: “I am continually amazed by what we find when we pause and take a short amount of time—six weeks or so—to do diligence ourselves and quantify full potential. I can’t imagine ever running a company now without doing this.”

[ 2 ] Build a Fit-for-Purpose Management Team

In public companies, executive teams often remain relatively stable for long periods—sometimes decades. But when conditions and strategic priorities change, long-tenured management’s bias toward the status quo can weigh a company down and entrench outdated assumptions about what it takes to succeed.

The guiding principle for PE-backed firms is straightforward: The CEO and the team must fit the company’s value-creating thesis; the thesis shouldn’t be designed around their capabilities. At the best portfolio companies, each top executive is held individually accountable for one or more value drivers in the thesis. For instance, if the thesis centers on digital transformation, the CMO might be responsible for shifting the business from a direct-to-consumer brand to one focused on digital channel growth—and for hitting specific targets like increased e-commerce revenue as a percentage of sales within 24 months. If a driver is operational efficiency, the CEO might hire a COO with expertise in supply chain optimization to own the effort to improve margins.

At PE-backed companies, CEOs and top team leaders are often brought in from the outside. Indeed, our research found that 71% of PE acquisitions above $1 billion changed CEOs, and 38% of them did so within the first two years of ownership. The CEOs the PE firms hire focus intently on securing talent not just in the C-suite but in critical, thesis-linked roles a layer or two below it. (This approach does present challenges. Finding exceptional talent is expensive and time-consuming for nearly all companies.) In fact, several portfolio company CEOs we interviewed referred to themselves as the “chief people officer.” As one explained: “Thirty percent of the value of our new thesis is from radical procurement savings that we must achieve in two years, so for this role I need to find the best procurement person on the planet, not just in this industry, and I’m not going to stop until I find them.”

Incentive structures play a critical role in PE-backed firms, where CEOs and leadership teams are often given substantial equity stakes or performance-based bonuses tied directly to key value-creation milestones. While that approach may not be feasible in all settings, other companies can still borrow heavily from this model by linking incentives more explicitly to value-driving initiatives and setting clear targets and milestones that align individual and team performance with enterprise goals. For instance, a procurement leader responsible for a major portion of spending might be evaluated on the number of competitive requests for proposal issued, the share of spending competitively bid out, and the speed of procurement decisions, in addition to hard savings targets.

A final difference to note: While we hear repeatedly from CEOs globally that one of their biggest regrets is not moving fast enough on underperforming executives, PE-backed firms make talent changes quickly. We also regularly see them hiring talent and putting incentive packages in place in one to three months—a process that often drags on for six to 12 months or longer inside large public corporations.

[ 3 ] Clean-Sheet Labor

Labor typically represents 40% to 80% of most companies’ total cost structure, yet many organizations fail to manage it with the same discipline they apply to other expenses. While routine capital expenditures—even something as simple as new office supplies—may require rigorous approvals, hiring decisions often proceed with minimal financial scrutiny. That inconsistency is particularly striking when you consider that each new hire represents a significant recurring expense.

CEOs of businesses owned by PE firms recognize that disconnect. To fix it, they implement robust controls for head count and focus on building lean, high-performing teams. As one leading tech CEO recently said, “Talent density beats talent volume.” Beyond generating immediate cost savings, this approach also creates more-streamlined organizations.

Portfolio companies often staff teams using a technique called “clean-sheeting,” which radically improves labor productivity. In our experience the groups that do it in a comprehensive and disciplined way can reduce total labor costs by 30% to 60% within six months. It involves four main steps:

Eliminating low- or no-value work. The first step is identifying and rooting out activities that don’t contribute to a company’s strategic priorities. Low-value work tends to creep in everywhere in growing organizations. Regularly generated risk and financial reports that no one reads or uses to make decisions are a classic example of this.

Centralizing workers in fewer locations. In many organizations departments are spread among dozens or many dozens of locations—and that doesn’t even account for the employees who work from home. One firm that we worked with, for instance, had 6,000 engineers in more than 60 locations. Every time employees are physically dispersed into small groups without strong leadership, there will be slack and underutilization. Centralizing them into a limited number of locations with high-quality supervision will increase their output measurably.

That said, consolidation isn’t a cure-all. Research shows that in certain situations remote and hybrid models can lower attrition and expand access to specialized talent, especially in tight labor markets. The key to consolidation is to be intentional about which roles benefit most from colocation. For example, early-career employees, teams handling complex coordination tasks, and functions requiring hands-on supervision are more likely to perform better in centralized hubs.

Shifting work to better performers. Data across our client engagements shows that when team members do similar tasks (as financial clerks, engineers, and IT support employees do, for instance), 50% of the team typically executes 80% to 90% or more of the work while also achieving greater quality and higher customer-satisfaction scores. In clean-sheeting, objective productivity metrics are used to identify the people doing a very small amount of work. Their work is then shifted to medium and high performers, who are given clear performance standards and better incentives. In the long run this increases engagement across the organization—because the better performers retained have higher engagement to begin with, and it rises even further when they see the company improving performance.

Rebuilding smaller departments with simpler structures. Once unnecessary work has been eliminated, teams have been consolidated, and tasks reassigned to high performers, the organization’s structure is redesigned to be much simpler and more effective. The people leading that effort start with a blank slate and add only the roles needed to deliver results. The goal is to keep “spans and layers”—the number of people each manager oversees and the number of management levels—lean and create a focused organization. Too often, organizational structures evolve through years of ad hoc changes and quick fixes, and no one ever steps back to ask whether the structure still fits the business.

This approach is not about indiscriminate layoffs for cost savings; it’s about creating more-productive, higher-performing teams and increasing long-term flexibility. Such teams make fewer errors and enjoy higher engagement while raising quality and devoting more time to customers. They help companies earn higher profits that can then be reinvested in R&D and marketing or other growth-related efforts.

One CEO of a PE-owned company told us: “I’m consistently amazed at how smaller, better teams with managed productivity metrics can regularly do the same work with better quality as teams two times the size. Perhaps even more exciting, we are seeing higher employee satisfaction and as a result higher Net Promoter Scores from our customers.”

[ 4 ] Eliminate Bad Revenue

Not all revenue is created equal. At PE-backed firms, the leaders understand that and regularly analyze revenue streams and eliminate unprofitable or low-margin ones that drain resources and dilute the focus of the organization. Many executives at public and family-owned businesses are familiar with customer profitability and its impact. But CEOs of portfolio companies are willing to manage revenue down to increase earnings and improve cash flow. That’s often difficult for public companies to justify, given short-term revenue pressure and investor expectations.

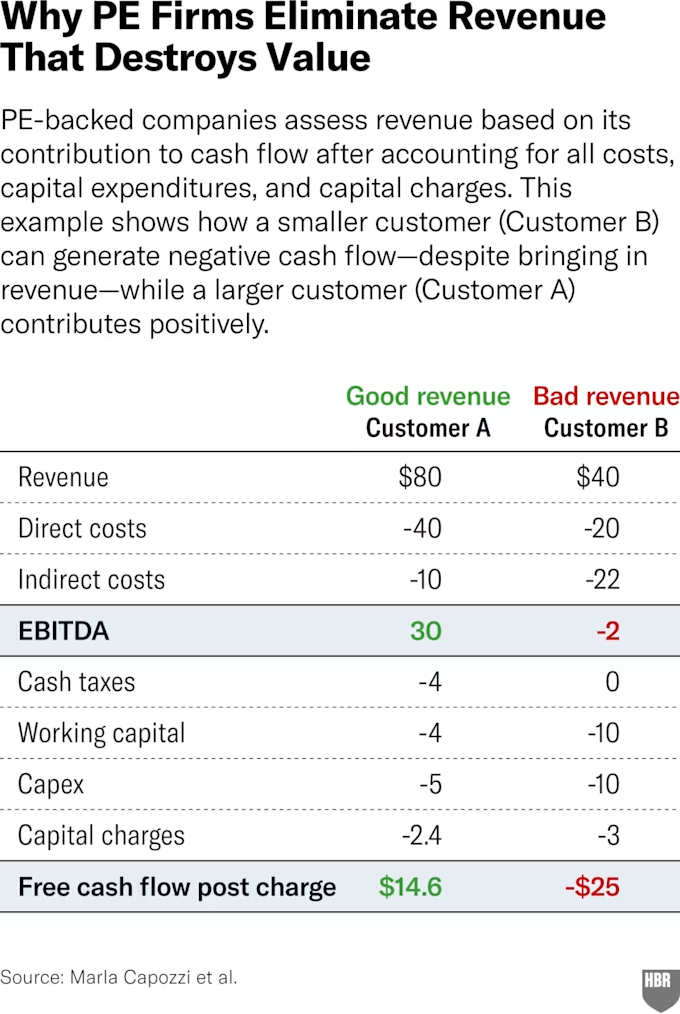

PE-backed firms can justify that approach because they focus on company valuations and understand that revenue growth won’t increase them unless it also improves cash flow—revenue after all direct costs, indirect costs, reinvestment requirements (working capital and capital expenditures), taxes, and a “cost of capital” charge have been accounted for. Good revenue increases cash flow, and bad revenue either reduces it or contributes less than the amount required to compensate debt and equity holders.

Consider two hypothetical customers that each generate significant revenue. (See the exhibit “Why PE Firms Eliminate Revenue That Destroys Value.”) Customer A contributes $80 in revenue, resulting in a positive EBITDA of $30, and after accounting for taxes, working capital, capital expenditures, and capital charges, generates about $15 in cash flow. This is good revenue. In contrast, Customer B generates $40 in revenue but has an EBITDA of negative $2 because of higher indirect costs. After further deductions for working capital ($10), capital expenditures ($10), and capital charges ($3), Customer B’s revenue results in a cash flow of negative $25. Clearly, Customer B produces bad revenue that diminishes overall profitability and drains organizational resources.

In our experience companies owned by PE firms address unprofitable customers in three major ways: First, they don’t just look at customers individually; they break the business down in multiple ways: by product, by region, and even by how different parts of the company operate. One tech company we worked with, for instance, analyzed profitability by product line and found a stark divide. Some products were generating strong cash flow—nearly $500 million annually—while others were dragging the business down. About a dozen product categories collectively had a negative cash flow of $223 million. By identifying and either fixing or phasing out these money losers, the company unlocked enormous financial value—nearly 17% more cash flow. Second, PE-backed firms don’t stop at the gross margin level. As we’ve noted, they ask whether a revenue stream generates cash for the business after accounting for everything it takes to support it: overhead costs like management and support functions, money tied up in inventory, investments in equipment and technology, taxes, and even the return investors expect to receive. This all-in view gives a far more accurate picture of whether a product or a customer is truly helping the company—or quietly hurting it. And third, they are more aggressive about executing these analyses and assigning people to remediate low-margin areas rapidly. Altogether, these actions help portfolio companies create significant value.

[ 5 ] Execute Relentlessly

Rapid execution is the cornerstone of private equity success. PE-owned companies need transformations more frequently and more quickly than most firms do. Their CEOs take a relentless, non-business-as-usual approach to implementing them, which can tilt the odds in a company’s favor.

Many of these CEOs break a firm’s value-creation thesis down into three to eight work streams and each work stream into dozens or even hundreds of initiatives. Every initiative will have a baseline, a business case, and an execution plan and (except for confidential initiatives) will be tracked in one common system that’s viewable across the company. Initiatives will be discussed weekly, and leading or lagging efforts will be explicitly celebrated or called out. A significant transformation agenda or persistent underperformance will be met by extra support or a leadership change.

This level of granularity ensures that progress is monitored in real time and that any issues get promptly addressed. The social pressure created by allowing everyone to see everyone else’s work stream encourages rapid change and improvement. Idleness or delayed decisions quickly become visible on the weekly dashboards.

Many CEOs tell us their job is to be the change agent who sets the agenda for transformation. Some appoint a chief transformation officer to instill discipline, prioritize activities, and track progress against objectives, although this may be a luxury in smaller PE-backed companies.

[ 6 ] Treat Time as Capital

Portfolio company CEOs are also expected to think like investors when managing their schedules, viewing time as a precious resource. Their boards and PE owners often encourage them to conduct regular analyses of their calendars to ensure that their time is aligned with the venture’s critical strategic priorities, especially the value-creation plan.

Boards of PE-backed firms will ask CEOs questions like: Are you spending enough time with top customers? Are you dedicating sufficient attention to the most critical value-creation initiatives? Are you spending too much time on tasks that should be reallocated to other management team members?

Treating CEO time with such care creates major benefits. For example, CEOs tend to overestimate how many hours they devote to critical strategic priorities while underestimating how many get eaten up by internal meetings and bureaucracy. In our experience CEOs perceive that they spend about 20% of their time on internal meetings. But a data-driven analysis of their calendars often shows that they spend 50% to 70% of their time on them. The CEOs who see this data are frequently very surprised by it, and almost all of them say they’d like to devote less time to those meetings.

Regardless of the actual percentages, the pattern is clear: How executives and managers think they allocate their time is rarely how they actually spend their time. The way to address this problem is to be disciplined about setting target time allocations for various priorities and then have your executive assistant track your actual time use and report it to you.

One CEO of a PE-backed company recently told us, “I clean-sheeted my entire calendar, took off every meeting, and freed up over 60% of my time and reallocated it toward my top strategic priorities. I plan to do this every year when I revisit my investment thesis.”

. . .

The practices that leading private equity firms use to generate exceptional performance in their portfolio companies should be of great interest to the boards, CEOs, and executives of other companies. Many of them can be directly transferred to other settings to generate higher financial returns as well as improvements in areas like customer service, safety, and employee satisfaction. While the constraints of public companies and family-owned firms may seem limiting, we believe the road map outlined in this article provides all managers with a blueprint for driving superior value creation.

Copyright 2025 Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation. Distributed by The New York Times Syndicate.

Topics

Payment Models

Economics

Strategic Perspective

Related

The Collaboration Imperative: Why Healthcare Executives Must Unite Against an Existential ThreatWhy Big Companies Struggle to Negotiate Great DealsMedPac Finds the Hospital Industry is on a More Stable Financial Footing NowRecommended Reading

Finance

The Collaboration Imperative: Why Healthcare Executives Must Unite Against an Existential Threat

Problem Solving

How to Make a Seemingly Impossible Leadership Decision

Problem Solving

Redefining Physician Leadership: A Comparative Review of Traditional and Emerging Competencies and Domains

Problem Solving

Bring Your Extended Leadership Team into Strategy Decisions