Summary:

Until recently most incumbent industrial companies didn’t use highly advanced software in their products. But now the sector’s leaders have begun applying generative AI and machine learning to all kinds of data—including text, 3D images, video, and sound—to create complex, innovative designs and solve customer problems with unprecedented speed.

For more than 187 years, Deere & Company has simplified farmwork. From the advent of the first self-scouring plow, in 1837, to the launch of its first fully self-driving tractor, in 2022, the company has built advanced industrial technology. The See & Spray is an excellent contemporary example. The automated weed killer features a self-propelled, 120-foot carbon-fiber boom lined with 36 cameras capable of scanning 2,100 square feet per second. Powered by 10 onboard vision-processing units handling almost four gigabytes of data per second, the system uses AI and deep learning to distinguish crops from weeds. Once a weed is identified, a command is sent to spray and kill it. The machine moves through a field at 12 miles per hour without stopping. Manual labor would be more expensive, more time-consuming, and less reliable than the See & Spray. By fusing computer hardware and software with industrial machinery, it has helped farmers decrease their use of herbicide by more than two-thirds and exponentially increase productivity.

Deere gathers data from all its modern farm equipment, including the See & Spray, as it’s being used. In total the company collects billions of measurements on soil, crop, and weather conditions from about 500,000 machines on more than 325 million acres of land. That data goes into Deere’s cloud-enabled JDLink system, where it’s analyzed and used to generate immediate and future improvements to the equipment and farms. Feeding all that information into machine-learning algorithms and AI enables Deere to create a portfolio of combined digital and analog services for optimal seed, fertilizer, and weed management.

Deere is one of the companies leading the way in the industrial sector. Until recently, incumbent manufacturers of construction and mining equipment and other heavy machinery didn’t use the most advanced software in their products. That’s no longer true. Today, using generative AI and machine learning, they extract insights and trends from structured and unstructured data—including text, high-resolution 3D images, voice interactions, video, and sound—and create complex designs in seconds.

Having studied industrial companies for more than 40 years, we’re fascinated by the way they’re now fusing analog machinery and advanced digital technologies. The smartest firms have come to realize that the deepest insights, rather than the most valuable physical assets, will separate the winners from the rest of the pack. But achieving success isn’t as easy as installing a computer in a tractor. There are many things to consider first.

The process starts with developing what we call fusion strategies, which join what manufacturers do best—creating physical products—with what digital businesses do best: using AI to mine enormous, interconnected data sets for critical insights. Industrial firms will have to figure out how to connect hardware and software, steel and silicon, and humans and machines. In this article we’ll describe four kinds of fusion strategies and how to execute them. They all require reimagining analog products and services as digitally enabled offerings and learning to create new value from the data generated by combined physical and digital assets. Just as crucially, industrial firms will need to partner with other companies to create ecosystems with an unwavering focus on solving customers’ problems.

How Fusion Strategy Differs from the Internet of Things

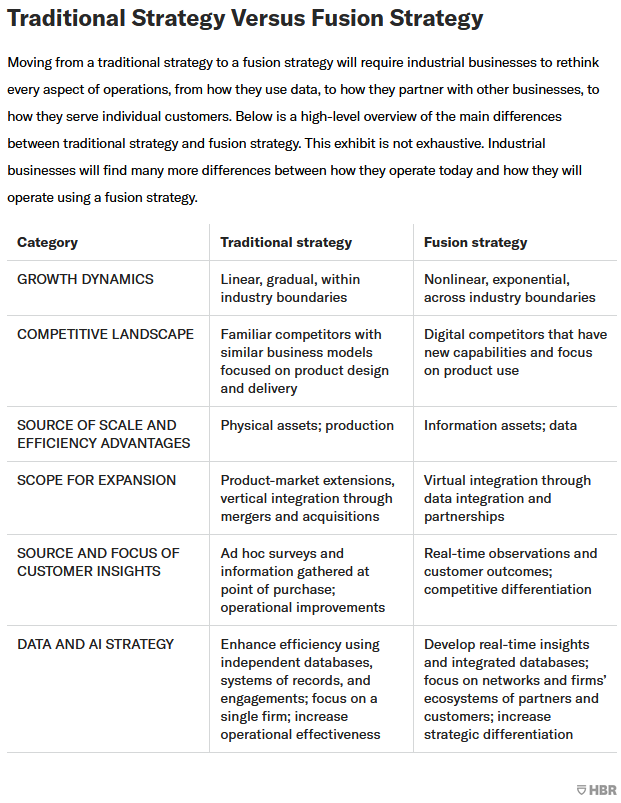

Traditionally, industrial manufacturers looked mostly at sales and marketing data. They analyzed it to see which demographic bought a particular product or which would be willing to spend more on a better product. Digital systems weren’t that important. The companies viewed them as a way to lower manufacturing costs or add features, such as Wi-Fi, to existing analog products. Today, however, industrial goods companies must also focus on what happens after the sale—on how combinations of digital and analog products enable positive outcomes for customers. Data on that must be gathered constantly, and insights from it applied in real time to customers’ problems.

Like the internet of things, fusion strategy involves a network of physical objects embedded with sensors, software, and connectivity. But fusion strategy goes beyond equipping an analog product so that you can monitor it and collect data from it over the internet. With fusion strategy, you completely reimagine how that analog product could be designed to function if it were built from scratch using every digital tool and functionality available.

Responsibility for fusion strategy is also handled differently in organizations. The internet of things is owned at the functional level, and use cases are straightforward: Managers in operations (such as supply chain coordinators and quality control executives) use the data from sensors to ensure that machinery-based processes adhere to specific industry standards and protocols. Designers build internet-enabled products that generate data that can be used in future iterations of those products. The separate functions don’t really have to coordinate their efforts. Fusion strategy, in contrast, is cross-functional. It requires senior-level executives from different departments to work together to determine how sensor data can be harnessed to deliver value to existing customers and to create new products for future customers.

Fusion strategy also generates insights and benefits more quickly than the internet of things does. While the machinery behind the internet of things ensures that data is recorded and logged, fusion strategy applies that data immediately, observing products’ use across diverse settings and then leveraging information on it to offer automated, personalized recommendations or experiences to customers.

The business case for fusion strategy is competitive differentiation. It’s about experimenting with newer technologies and developing a road map for incorporating them to get an edge. You can see this happening with the automotive companies that are developing self-driving vehicles. They will invest in the internet of things to adhere to safety standards, but the real differentiation they gain is in how sensors, software, and data connectivity are integrated to make their cars perform better than competitors’.

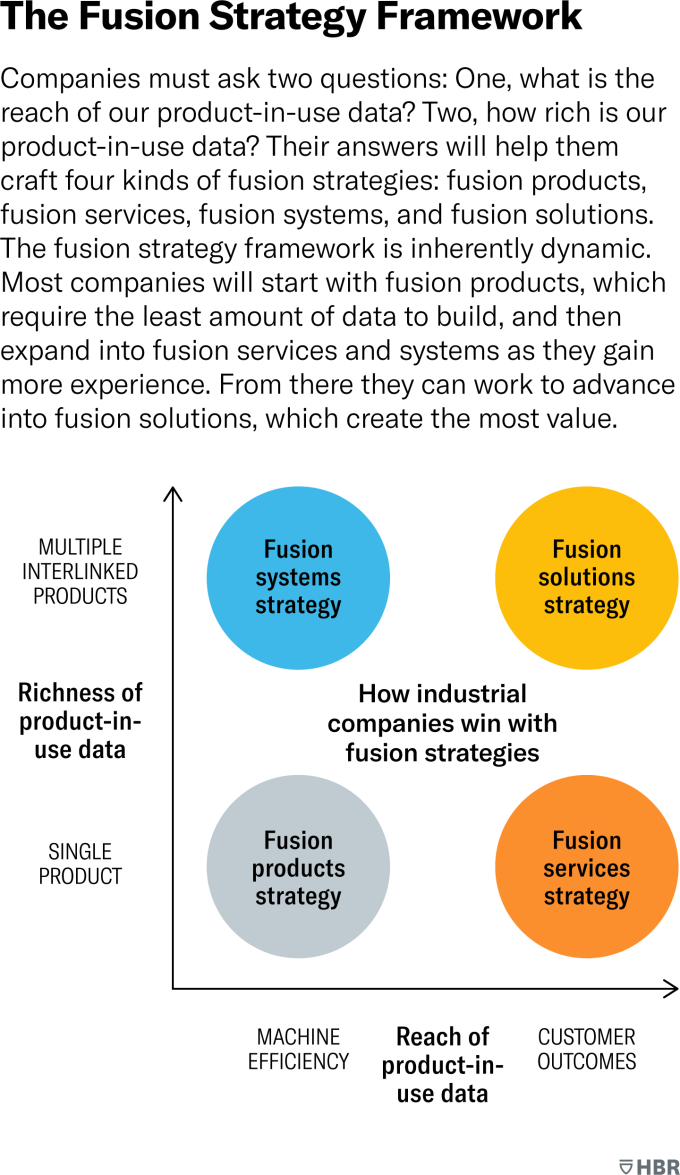

The strategic opportunities presented by traditional and generative AI and other advanced digital technologies fall into four main categories: fusion products, fusion services, fusion systems, and fusion solutions. Although most companies should start by focusing on fusion products, they should also explore and test the three other strategies. Experimenting with all four fusion strategies will allow them to determine how they can create and capture value, evaluate how other companies’ strategies threaten them, and determine how best to allocate their resources.

Fusion Products

As we’ve noted, fusion products are designed from scratch to collect and leverage information on products’ use in real time. The amount of data they generate is increasingly massive, and companies can apply AI to it in three ways: They can use traditional AI to analyze it for, say, potential product, process, and cost improvements; they can use generative AI to create digital twins of existing products (virtual duplicates that mirror their functioning) and train robots; and they can use the large language models within generative AI to develop proprietary insights that will add value for customers.

Take Tesla automobiles. They were designed from the start to be cloud-connected computers on wheels. For more than three decades incumbent automakers have added digital features to their products, including GM’s OnStar, Ford’s Sync, and Mercedes’s Mbrace, but those features didn’t enable the companies to track automobiles in real time, analyze data continuously, and improve vehicles on the fly the way Tesla does. The sensors in every Tesla provide immediate information about how it’s performing on the road. AI determines whether it is working optimally or needs fixing, and in many cases Tesla is able to correct problems with software updates. Tesla can stop a door from rattling by tweaking the hydraulics, for example, or it can adjust regenerative braking levels with over-the-air software updates to reduce collision risk.

Today, rather than using an army of on-site technicians, industrial companies can let customized recommendations generated by AI flow automatically to customers.

Tesla is now experimenting with using generative AI to program autonomous vehicles. By studying video data taken from inside every Tesla, generative AI can reconstruct multitudes of driving scenarios, which Tesla can then use to train cars to avoid collisions and other dangers.

In each Tesla an operating system, which houses data from all the vehicles, helps it respond quickly to insights from hundreds of thousands of cars. The system integrates three digital twins: a virtual rendering of the car’s model as it was designed (the product twin), a virtual version of the assembly line that created it (the process twin), and a representation of the product in use (the performance twin). The system also incorporates insights gathered from Tesla’s supply chain, manufacturing operations, and after-sales services.

Tesla’s competitors are now trying to catch up by developing their own original fusion products. Mercedes is focusing on designing AI-enhanced operating systems for its vehicles and has teamed up with Nvidia for software, hardware, and AI chips. GM, partnering with its subsidiary Cruise, already has put self-driving taxis on the road. (Although last fall it had to withdraw them after their safety came under question, once GM understands the causes of safety lapses, it will probably resume operating the taxis.)

Fusion products can be found in other industries too. The window manufacturer View, for instance, has developed smart glass that uses real-time data and AI to automatically adjust how much sunlight gets in. When natural light in a room is low, the glass allows more in, but if the room gets too hot, it will filter sunlight out.

Early movers can capture value from fusion products in several ways. The most attractive option is to charge premium prices for them—as Tesla does. Product makers can justify higher pricing if their offerings perform better than those of rivals and cost less to operate. Another option is to offer performance contracts to guarantee that fusion products will be proactively maintained and updated, ensuring minimal downtime. Rolls-Royce is one company that does this. It guarantees uptime of close to 100% for its commercial airline customers by using AI to monitor and maintain the engines in planes. When something fails on one of its engines, Rolls-Royce knows about it in advance or finds out in real time, which allows it to troubleshoot the problem much more quickly.

Another way to capture value is to use fusion product insights to enter adjacent spaces. Tesla, for instance, has gone into the automobile insurance business and can offer rates that are lower than the competition’s because of its ability to record and analyze the behavior of individual drivers instead of clustering them into different risk profiles, which is how other insurers operate.

Fusion Services

Until now services related to industrial goods have been labor-intensive to deliver, with businesses relying on codified knowledge and standard protocols to fix problems. Though it’s more profitable to deliver customized services quickly and in large volumes, doing so was difficult and expensive in the analog world. But today, rather than using an army of on-site technicians to provide services, industrial companies can let customized recommendations generated by AI from product-in-use data flow automatically to customers.

New ventures have already jumped on this opportunity. For instance, weather and climate data from companies such as Weather.com and ClimateAi allows farmers to make precise decisions in a timely manner and enhance profitability. Norm, a ChatGPT app for agriculture, mines available data on weather, soil conditions, and current events to answer all kinds of questions about farm management.

Some established industrial companies have gotten into fusion services too. In the civil aviation industry, improving aircraft engines’ fuel efficiency by 1% could save $2 billion a year. Rolls-Royce’s R2 Data Labs saves its customers $200,000 per aircraft annually by analyzing the fuel consumption patterns revealed by product-in-use data, such as the routes planes take, the altitudes and speed at which they fly, weather conditions, and the loads they’re carrying, and then relaying the insights to customers in real time.

In their early stages, fusion services can be sold through unbundled pricing, with buyers paying only for services they find valuable. As customers’ appreciation for the services grows, industrial companies can migrate to offering bundled packages of services. Over time they could even enter into gain-sharing agreements that give them a percentage of the increase in profits that their fusion services generate.

Fusion Systems

Many customers of Deere and of other makers of farm and construction equipment use complex systems that include multiple kinds of machines, each of which is made by a different specialized supplier. Most customers manage the interoperability of these machines themselves, but some hire systems integrators and consultants to install, connect, and upgrade them. Digitization can make operating them a lot easier. But with fusion systems, it shifts from a micro level (enhancing products from different companies independently to improve their efficiency) to a macro level (enhancing multiple related products from multiple companies in concert to improve the whole system’s efficiency).

A fusion systems integrator must not only connect all the machines and equipment it has sold but interlink them with those of partners and competitors. And instead of being responsible just for interconnecting different elements and getting the system to work, as traditional systems integrators are, the creator of a fusion system must ensure that it improves continually as new parts and functionality are added.

This is where AI plays a key role. Most industrial goods companies are comfortable synthesizing structured data such as names, addresses, credit card numbers, and other easily formatted customer information. But the advanced firms feed unstructured data—like images of defects, the sound of faulty machines, and video feeds of autonomous processes—into generative AI in real time to develop complex, realistic digital twins of systems. They can then use those twins to experiment with mixing and matching different permutations of products, machines, components, and peripherals to determine which combination of technologies works best.

Dubai’s Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building, employs numerous systems—for ventilation, air-conditioning, lighting, water management, parking, storage, elevators, telecommunications, and security—in its overarching facilities-management system. Honeywell collects real-time data from the building’s intricate system and analyzes it to identify anomalies, such as malfunctioning equipment. It helps Burj Khalifa detect incidents earlier, react faster, and mitigate potential risks. That strategy has reduced the maintenance time for Burj Khalifa’s mechanical assets by 40% while improving their availability to 99.95%.

Fusion systems are likely to change the buying preferences of customers. They may shift from focusing on products with distinctive features to focusing on products that can be integrated with other products. Because of this, industrial manufacturers must create technology architecture that integrates hardware, software, applications, data, and cloud connectivity and can incorporate product-in-use data and algorithms from other products. Industrial companies will monetize the value their fusion systems create through integration fees as well as charges to connect additional machines. They can also generate revenue by selling fusion-systems software as a service through onetime license fees, monthly subscriptions, or a pay-as-you-go model.

Fusion Solutions

Fusion solutions combine fusion products, services, and systems in ways that directly improve a customer’s performance. Rather than developing solutions through traditional consultative sales processes that approach each customer problem as a one-off, companies develop them with insights from product-in-use data and design them to be applicable to many customers. But designing these solutions effectively requires industrial companies to be experts at solving customer problems in ways that no other company can. They must earn an unusually high level of customers’ trust, and they should tie their revenues and profits to customer success using outcome-based contracts and profit-sharing agreements (as they may eventually do with fusion systems).

To create the greatest value for customers, industrial companies will have to partner with other businesses to develop ecosystems of solutions. Deere, for instance, has teamed up with the agricultural software company Granular, which uses unstructured data to develop yield models for farmers. Granular’s models collect and analyze imagery from satellites, gathering information on weather, elevations, and soil conditions, and combine that data with historical yield statistics to help Deere’s customers forecast costs, revenues, and profits. As it sells fusion solutions to the market, Deere will go head-to-head with traditional competitors such as CNH Industrial and AGCO, but it will also compete with software companies, such as the Climate Corporation, now part of Bayer, and digital giants like IBM and Alphabet. Ultimately, the battle for customers will be between different fusion ecosystems, not individual companies. While each fusion strategy creates pools of value for businesses, by combining them all, fusion solutions will create the most value.

. . .

Every industrial company will have to develop its own fusion strategy. The first step will be to stop treating human intelligence and machine intelligence as if they were separate. Every function and process can be enhanced if humans and machines work together. The companies that embrace that kind of collaborative intelligence will outperform those that treat AI as an esoteric technology or postpone its adoption.

Until now industrial companies have competed by developing proprietary technologies and integrating vertically. To execute fusion strategies, most will have to partner with digital natives and start-ups on new technologies and applications, but doing so will ultimately lower costs, increase speed, and improve customer satisfaction. This will be a major shift, however, and will require industrial CEOs to lead digital efforts—a responsibility they’ve usually delegated in the past. Their firms will need a holistic strategy for how, when, and where digital technologies will drive the organization to ensure that everyone in it shares the same view of priorities and resource allocation needs. And every employee will have to embrace digital technology in order for the organization to craft, execute, and adopt a fusion strategy that succeeds.

Copyright 2024 Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation. Distributed by The New York Times Syndicate.

Topics

Technology Integration

Healthcare Process

Environmental Influences

Related

They Need a Ventilator To Stay Alive. Getting One Can Be a Nightmare.Healthcare Insights: Curated for HALM January/February 2026Managing a SlobRecommended Reading

Quality and Risk

Healthcare Insights: Curated for HALM January/February 2026

Operations and Policy

Managing a Slob

Operations and Policy

Managing Your Team’s Weakest Link

Strategy and Innovation

How to Use Gamification to Engage Your Team

Strategy and Innovation

Financial and Economic Issues