Organizational culture can mean different things to different people. Although difficult to categorically define, from a leadership perspective, organizational culture has been described as an organization’s “immune system,” and more broadly as “unwritten rules, silent language, unseen.”(1,2)

Culture also incorporates shared beliefs and values, which drive behavior. Because it is nebulous, culture lacks other measures of leadership success such as strategy. The triad of strategy, purpose, and culture are all important in driving the success of an organization(3) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Importance of Culture in Organizational Success and Performance

Culture is distinct from strategy in one important way. Whereas culture is more a standard of behavior accepted by all employees, strategy is typically determined by the C-suite and seen as providing “clarity and focus for collective action and decision making.”(2) Most importantly, a strong culture widely shared by leadership enhances organizational performance, reduces turnover, and keeps everyone focused on positive results.

The saying “culture eats strategy for breakfast,” attributed to management guru Peter Drucker, clearly suggests the importance of physician leaders paying close attention to culture and how it impacts organizational performance. The significance of culture in the workplace is confirmed by a recent survey of physicians that shows that they want satisfaction with their work, effective use of their skills, and compatibility with the organizational culture.(4)

THE IMPORTANCE OF ASSESSING AND BUILDING CULTURE

As chief executives, new physician leaders must determine how to spend their limited time. Should they start by focusing on the mission, vision, strategy, purpose, or something else? While all those aspects of the organizational culture are important and each must be thought through both short-term and long-term, assessing and building culture is the most critical leadership skill, as it emphasizes team-based and value-based healthcare.(5) And yet, it may receive the least attention of all.

This lack of attention is partly because it is hard to encapsulate the desired culture in a statement or a few lines on a website. Doing so requires multiple observation of behaviors, feedback loops, and time to discern unhealthy behaviors. The process then requires repeated communication to instill the desired positive behaviors to bring about culture change. Indeed, guiding a shift to the desired culture and emphasizing the anticipated positive aspects of that shift is an important part of managing overall organizational change.

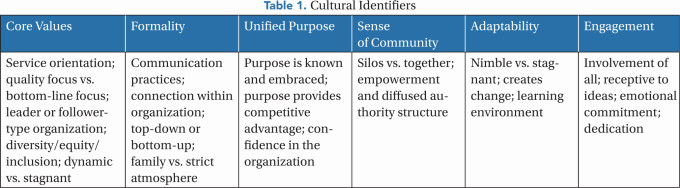

While contemplating changing organizational culture, it is important to remember that these changes take root over time, whether the framework is governance, quality of care, or behavioral and personnel issues. Furthermore, there are nuances to observing the existing culture before opting to institute changes. Some key cultural identifiers are shown in Table 1.

Kotter and Heskett advised that there are two levels of culture within organizations: one fully visible and the other less visible.(6) A fully visible culture includes the work environment, office design, and dress code. In contrast, a less visible culture may include an unexpressed belief system or commitment to duty and loyalty.

Whereas new leaders and employees are initiated in behaviors associated with the obvious culture, which may be easier to change, the hidden culture, which is not immediately noticeable, is more difficult to change (Figure 1). In this context, many people embedded in an existing hidden culture may not be disturbed by isolated events; they often do not appreciate the totality of unhealthy behaviors and their impact on the organization and its performance.

MAINTAINING MARKET LEADERSHIP

By necessity, healthcare organizations must focus on a strategy to maintain their positions as market leaders. An important part of any strategic plan is differentiating the institution from its competitors. An essential differentiator is the culture of the organization and how it affects performance and success.

Culture appears to be underleveraged in most organizations, including healthcare systems.(7) Although senior leaders recognize culture as a competitive advantage, there is a large gap between viewing culture as critically important and managing it effectively.(8) In an international survey of more than 6,000 leaders, 72% indicated that culture was an important driver of performance; yet they ranked creating and maintaining culture 12th.(9)

There also may be a financial link associated with a healthy culture. Two-thirds of 500 senior executives of the world’s most admired companies attributed 30% of organizational success to their company’s market value and one-third attributed 50% of organizational success to their culture.(10)

MAKING THE CASE FOR CULTURE CHANGE

A challenging task is convincing the workforce of the need for culture change. In this regard, Hollister and colleagues wrote, “If your culture needs to change, how should you approach working on it? The first step is to recognize that culture change is hard work. It’s challenging enough to change one’s own habits, never mind those of thousands of employees.”(3) They also contend that many people in the organization may see existing norms as part of its success and therefore, other than in a crisis, have no desire to change. This may be the most challenging aspect of physician leadership.

Hollister and colleagues also suggest that leaders who want to change culture must understand and follow these focused precepts: “1) Recognize that responsibility for culture cannot be delegated. 2) Start with the ‘why.’ 3) Define the target cultural values and behaviors. 4) Engage and get input. 5) Build a bridge to the future desired culture. 6) Build a culture road map. 7) Reinforce the desired culture in all organizational systems. 8) Rapidly reward the emerging culture.”(3)

Bringing about cultural change requires more than posters, huddles, and “all hands-on deck” meetings. The incoming leader must start the process by doing a structured culture audit, conferring with hospital executives and clinical leaders, as well as employees at various levels of the organization. Then, the physician leader must frame the key issues that matter and use every lever available to guide the organization forward. Leaders must also articulate their aspirations and vision that fits with the desired culture.

Evoking the message and modeling the way forward is a powerful tool to spread the word and reinforce positive behavior. For instance, if the desired culture values receptiveness to change, the senior leaders must exhibit that behavior themselves, then monitor and tweak the change. Some organizations teach their leaders that culture starts at the top and that leaders should be “culture champions” or role models and “culture architects” who build the structures necessary to support desired behaviors.(11)

Subsequently, a leader should clarify the alignment of the values viewed as important to the institutional culture and the behaviors that are valued and rewarded. An example would be measuring and then setting up a few critical behaviors consistent with the desired values — maybe no more than three or four to start with as part of “repairing” the culture. In a healthcare environment, the values could be empathy, collaboration, accountability, and learning.(10) These values must then be communicated regularly to all groups, teams of employees, and executives.

As the message is disseminated, the leader should meet with human resources personnel, search committee members, and clinical leaders to ensure they are familiar with preferred values and behaviors and can then assess new applicants for congruent values.

UNIQUE CHALLENGES

The time and effort needed to identify the existing culture and the desired changes varies based on the organization itself. Academic institutions present some unique challenges. Organizational culture at academic institutions is distinctly different from other not-for-profit or for-profit healthcare organizations for many reasons.

In general, academic organizations are more hierarchical, driven by teaching and research in addition to patient care, and may be more resistant to change. Their governance system is also more complex, depending on their affiliation. This makes academic medical colleges slow to pivot and be more inflexible in making decisions in a rapidly changing healthcare environment.

The hurdles may be political. Lindsey Dunn quotes Ora Pescovitz, MD, then CEO of University of Michigan Health System, as saying, “Where we need to improve is in our ability to be more nimble, more flexible, and more adaptable. That requires a culture that is prepared to evolve. We’re not as adaptable or responsive as our competitors.”(12)

In many organizations, leadership communicates too many change priorities for employees to remember, let alone act on. Therefore, new leaders must recognize that needed change will struggle to make headway within the existing framework if the default culture is unhealthy and there is no prioritization.

In addition, some academic deans may not be in touch with rank-and-file faculty, since the new leader experiences the existing culture primarily from secondhand information rather than in face-to-face conversations or group meetings.

However, a new leader may have a small advantage with a fresh set of eyes or what Batista calls “newbie goggles” and may find it easier to spot culture issues.(13) As he points out, changing anything, let alone the culture, creates problems and risks failure if done too fast without adequate understanding. Therefore, it behooves the leader to spend some time and find some acceptance as a member of various groups in the institution before embarking on the culture change.

INVESTING FOR RECRUITMENT AND RETENTION

One often-overlooked aspect of culture is its impact on recruitment and retention. Much of the recruiting process at the leadership level focuses on shallow discussions about the job description and how the personalities of the candidates fit with those interviewing them. Those personnel who are managing the leadership search must be familiar with the existing and the desired organizational culture and ensure that a dialogue takes place with candidates about the desired culture as well as the culture at the candidates’ current organizations.

Another challenge for healthcare organizations is workforce retention in the face of what is now being called “the great resignation.” Organizations are therefore investing in many programs such as signing bonuses, competitive compensation, wellness, and leadership training programs.(14) Managing culture for organizations becomes even more important for leaders who are trying to retain and hire newer generations who have different views and attitudes.(15)

References

Watkins MD. What Is Organizational Culture? And Why Should We Care? IMD. February 2017. https://www.imd.org/contentassets/63bf6add29e046f1af6b2c48dc81da21/tc008-17.pdf

Groysberg B, Lee J, Price J, Cheng Yo. The Leader’s Guide to Corporate Culture. Harvard Business Review. January-February 2008. https://hbr.org/2018/01/the-leaders-guide-to-corporate-culture .

Hollister R, Tecosky K, Watkins M, Wolpert C. Why Every Executive Should Be Focusing on Culture Change Now. MIT Sloan Management Review. August 10, 2021. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/why-every-executive-should-be-focusing-on-culture-change-now .

Ryan PT, Lee TH. What Makes Health Care Workers Stay in Their Jobs? Harvard Business Review. March 2, 2023. https://hbr.org/2023/03/what-makes-health-care-workers-stay-in-their-jobs .

Gittlen S. Culture Is What You Do, Process Is How You Do It. NEJM Catalyst. August 7, 2017. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0438

Warrick DD. What Leaders Need To Know About Organizational Culture. Business Horizons. 2017;60:395–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2017.01.011

Aguirre D, Post R, Alpern M. Culture’s Role in Enabling Organizational Change. PwC. 2013. https://www.strategyand.pwc.com/gx/en/insights/2002-2013/cultures-role/strategyand-cultures-role-in-enabling-organizational-change.pdf .

Organisational Culture: It’s Time to Take Action. PwC. 2021. https://www.pwc.com/culture-survey .

Miller M. How Culture Can Be a Competitive Advantage. Smart Brief. March 8, 2023. https://corp.smartbrief.com/original/2023/03/how-culture-can-be-a-competitive-advantage .

Korn Ferry. How the World’s Most Admired Are Shaping Culture. 2023. https://www.kornferry.com/insights/featured-topics/organizational-transformation/how-the-worlds-most-admired-are-shaping-culture .

Burnison G. Culture: It’s How Things Get Done. Korn Ferry Insights. 2014. https://www.kornferry.com/insights/special-edition/how-things-get-done .

Dunn L. Why Culture Trumps Strategy. Becker’s Hospital Review. January 17, 2014. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/healthcare-blog/why-culture-trumps-strategy.html .

Batista E. Newbie Goggles. Blog. April 24, 2022. https://www.edbatista.com/2022/04/newbie-goggles.html .

Tung J, Nahid M, Rajan M, Logio L. The Impact of a Faculty Development Program, the Leadership in Academic Medicine Program (LAMP), on Self-efficacy, Academic Promotion, and Institutional Retention. BMC Medical Education. 2021;21:468–480. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02899-y .

Economy P. Why Are Millennials So Unhappy at Work? Inc. February 4, 2016. https://www.inc.com/peter-economy/why-are-millennials-so-unhappy-at-work.html .