According to the website evariant.com, “Physician engagement is a strategy aimed at creating stable relationships between physicians and hospitals or health systems and is a critical success factor for navigating the delivery system transformation. An engaged physician correlates with enhanced patient care, lower costs, greater efficiency, and improved patient safety, as well as higher physician satisfaction and retention.”(1)

As the definition notes, stable relationships are the key, but we expand this beyond hospitals and health systems to include payers, and suppliers of equipment and supplies. To effectively manage the practice, leadership must be involved with, or at least have a solid understanding of, each relationship to successfully follow the strategic plan.

Relationships

Every day we talk with countless individuals, including patients, staff members, other providers, and vendors. All these individuals are treated as our customers, and we continually relate to them through each interaction. The technical aspect of the world — the internet, blogs, emails, social web sites, etc. — takes away some of the personal, face-to-face, time that existed in the past. However, there is still a relationship between the one who sends the message and the one who receives the message.

These relationships, personal and technological, require effort to develop, maintain, and enhance. Several years ago, an article by David Wilson was published suggesting that there are key factors in building relationships.(2) These key factors are expanded in Figure 1. These keys will ensure success in personal, as well as in business relationships.

Figure 1. Relationship building blocks.

Essentially, a strong relationship is built on trust. If you can’t trust someone, how can you have a long-term relationship? How you build that trust is key to achieving commitment, compliance, and cooperation. These three “C’s” represent the desired outcome.

Let’s start on the left side of Figure 1:

Social bonds. The ice breaker in building a relationship is getting to know each other socially. This involves asking questions about someone’s family, interests, hobbies, etc. You may find out how many children they have, where they went to school, if they like sports, and so on. It is also necessary to notice unspoken characteristics, such as the type of clothing worn, and if their office has pictures and paraphernalia on the wall or desk. These factors can help lead to future conversations. This social bonding will help with the next encounter. Keep in mind that the provider can ask a lot of questions, but so can the front desk staff and triage team. Make sure to note these social items in the EMR to help everyone in the office get to know the patient better.

Mutual goals. When building a relationship with someone, you need to know what is important to them, what they expect from the relationship, and what makes up their own personal goals. There is a purpose in all relationships based upon the expectation or goals that contribute to why the relationship exists in the first place. In a provider–patient relationship, the mutual goal might be to get well or, at the very least, to have an improved quality of life. In a sales relationship (for example, when a patient needs surgery and there is a sell required), the mutual goal would be to reach agreement on the price, service, etc. of an item.

Power/dependence. Like it or not, there is not only a mutual aspect in any relationship, but also a power position. One of the individuals involved has control most of the time, but which individual this is may vary and change based upon circumstances. In the provider–patient relationship, who has the power? Often it is the provider, who is leading the Q & A portion of the visit and instructing the patient what needs to be done to achieve the mutual goal of getting well. However, the patient may be in the power position when it comes to talking about their needs initially, or in complying with the proposed care plan. This dynamic is in a constant state of flux with the advent of the internet, and the incredible amount of information that is now available to the patient. The patient may have their mind made up on the diagnosis and treatment plan prior to arrival, which begs the question who is in control, and how do you deal with it. The power position suggests that there is always one dependent on the other in a relationship. This also applies internally. A new employee is dependent upon their coach to learn, but later the coach is dependent upon the employee to perform their assigned duties. This is not a negative context, but a real role definition. If either the power or the dependence becomes too dominant, the context turns negative, and the relationship is destined for failure.

Structural bonds. Any organization has a structure, whether it is written as an organizational chart or not. This formal approach to a relationship is necessary to ensure that everyone knows where they fit and how they work with others, and to consistently fulfill the mission. There is also structure in the very nature of the provider–patient relationship, with the provider as the assumed leader. However, here is a good place to also point out that there are structured relationships that are informal. These will have the power/dependence aspect to them. Many times, these informal relationships are very beneficial, but they also can be a problem in the organization.

Communication. Enough said! Well, not really. None of the aspects of the relationship are possible without effective communication. There is a sender of the message, and a receiver — a talker and a listener. Listening is an art that requires focus. Beyond the obvious verbal communication is the nonverbal, or body language, message. Asking questions of a patient, but looking at the computer screen, may send a message of disinterest or not caring about what is being said. Crossing arms in a conversation also may be telling, implying you are closed off to the receiver. In the electronic world, capital letters are interpreted as screaming. It is difficult to really understand what someone is saying, or their intent, in an electronic communication. Many times, the nonverbal, facial expression or the direct opportunity to ask for clarification is missing, which makes the communication process incomplete and ineffective.

Consistency. Without consistent communication, there is no way to know what will happen next or what to expect. The key point here is that sending a message that is authentic, and doing it regularly, will help build the relationship with the other party.

Compare alternatives. There are over 7 billion people on earth, and therefore there are alternatives. In some case it is best to choose the alternative, but in other cases it is best to recognize that there are alternatives, but that what you have chosen is the right one. This concept becomes very important to remember for the provider and the entire staff of the practice. The patient has a choice, and if the relationship is not built on all the points we have discussed, they may choose an alternative provider. There is always another applicant for a position. The alternative concept should be in the forefront of your mind in developing a relationship, especially with those who you serve.

Compassion. Compassion is defined as “sympathetic consciousness of others’ distress together with the desire to alleviate it.” The patient is looking for a compassionate aspect of the relationship. In most cases, the discussion about the patient’s condition requires understanding, as well as an offer of support.

Trust. There are many other terms that could be used, but I believe these are the basic building blocks leading to a level of trust. Merriam-Webster defines trust as “assured reliance on the character, ability, strength, or truth of someone or something.”(3) The basis of any relationship, then, is built on the idea that we trust the other party. If you cannot trust someone, how can you have a positive relationship? You may not trust someone and still have a relationship, but it will not lead to any of the three “C’s.”

The right side of Figure 1 suggests that the outcome of all of the above is a commitment to the relationship. The business and the individual expect and desire the long-term commitment. After all, it is easier, and cheaper, to maintain a relationship than it is to build one. A committed relationship will also benefit as a compliant one. The provider will be able to offer a better relationship, and achieve mutual goals, if there is compliance with the agreed-upon care plan. This means there is full cooperation on the part of everyone, including the patient’s commitment that the prescription is refilled in a timely fashion to ensure health is achieved. As we look at the future of healthcare, patient compliance with the treatment plan is essential. It may not be a valid “C” in the perspective of most relationships, but it is still worth thinking about.

This is obvious when you think about the partner relationship or the employer/employee relationship. It is obvious when you consider the provider referral and the vendor/customer relationship. But as time moves forward, the need arises to build better relationships with the payers, the hospital “C” suite, other providers who may be competitors, employers, government officials – regulators or elected, and others that you may have in your local community.

The main message is the goal of approaching relationships in a structured manner, keeping these key concepts in mind.

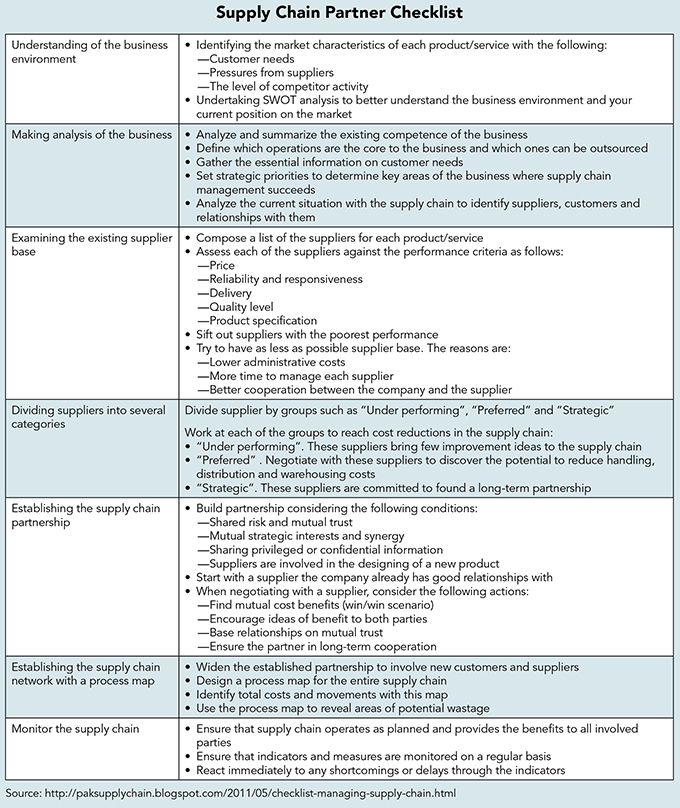

Let’s take a page from industry and apply it to our healthcare world. The manufacturer of a widget requires materials from others to complete construction. There may be one, or many, suppliers that require coordination and negotiation of items such as delivery time, amount, and price, information, and communication. This is referred to as a supply chain, where suppliers provide and meet the needs of the customer. Who has the power in this relationship, who benefits, and how do they benefit? In successful supply chains, all parties benefit from the relationship; this mutual partnership is key to each one’s success.

A supply chain in healthcare may be as simple as patient to provider, or payer to provider. But in most cases, there are multiple players involved in meeting the needs of the ultimate customer. These include payer, hospital, clinic, equipment supplier, drug supplier, and many more. It is in this context that the individual practice lives and, hopefully, survives.

To accomplish this effort, there are three major barriers that must be overcome. First to explore is the individual focus, beyond just the physician’s role. Second is the tone of the organization itself, and the support structure in place to allow time and compensation to encourage involvement in tasks that are necessary for the organization to succeed. And finally, there is a need to understand the nuances of the outside world. This includes everything from the motivation of the partner to the role and influence of government laws and regulations.

In today’s population health value-based payment world, creating and maintaining partnerships that have common purpose, willingness to share data, and recognition that each member of the supply chain will benefit by working together, will lead to mutual wins. This requires open communication; understanding each other’s goals, objectives, and needs; and the ability to work within those parameters. The openness required may mean joint planning meetings.

One can look at the payers with their emphasis on medical home models for both primary and specialty providers. They have significant data on the practice that they should be willing to share. The practice needs those data, along with their own data, to ensure that it accepts a payment level and quality metric level that is attainable. The payer must recognize the upper-level providers and acknowledge that they are better off with those entities in their networks. A win-win is possible by being open to each other.

A partnership model might look something like what is illustrated in Figure 2.(4) There are driving factors, or reasons, to enter the partnership, including a supportive environment, and the activities and processes that will make the relationship work. An important question to ask is if you drive or if others drive, and this perspective makes a difference in how you perceive the key aspects of the model.

Figure 2. Relationship-based business model.

Drivers with payer partners will include reimbursement amounts, quality metrics, contract termination terms, pre-authorization waivers, timely filing requirements, and other items. Drivers with suppliers will include pricing, rebates, delivery times and amounts, variety of products available, and the ability to contact the right person. Drivers with hospitals will include access to services, privileges, reporting, hospitalists, ED support, quality metrics, and information exchange.

A key point in developing partnerships is your identification of who you will choose as your partner. This is not just an externally based decision. Rather, it starts internally. Multiple physicians have multiple opinions of products, hospital systems, referral sources, drugs, and the like. Therefore, internal discussions will need to occur. For example, many hospitals face decisions on what knee joint replacement vendor should be used, as surgeons will have different opinions. This may not seem as big of a factor internal to the practice, but these discussions must occur. It is not advantageous to have two or three vendors for similar products. The practice is better off having the lengthy, difficult discussions internally before seeking a partner, rather than spending resources developing relationships only to have them fall apart due to lack of support internally.

Factors to consider reach beyond limiting vendors on supplies. One payer may consider a key procedure as experimental and have a long history of not supporting the innovative modeling that you do. Therefore, all other factors may be great, but a key procedure in your internal strategic plan may not be supported, or there are no plans for a payer to support that procedure.

Obviously, you cannot have a successful partnership without a high level of trust with your partners. This is created through factors such as consistency, responsiveness, open communication, social norms, and much more.

How does your partner work? Digging deeper into who makes decisions, as well as when and how are they made, is a key to good working relationships. Neither partner has time to waste. If travel is an issue, can you communicate effectively via a digital model, or is face-to-face the best? Or better yet, what issues require face-to-face interaction? It is important to make appropriate plans for those communications to occur.

Supply and demand will play a big role. Does the payer offer a solid list of employers, or other patient sources? Who are the employers, and are you cut off from accessing them directly for wellness programs, etc.? Or is there a partnering way to achieve population health objectives?

Partners may best be chosen by recognition of, and/or elimination of, the competition. The competitor may offer the same type and quality of service that you do, but the employer base, geographic location, or other similar factors may make a relationship with a partner desirable.

The vendor must be able to provide products when needed, making it important to consider if they can be delivered the next day, or if delivery will always be delayed a few days. The demand for the supplies from the practice can be developed and managed on a “just in time” model. The “time” can be defined differently, such as next day or two days. Very few applications in the office would require same day. But delivery is critical, since it directly affects the amount of inventory the practice must have on hand, and reduces the funds tied up in inventory. Historical data, and the use of predictive analytical tools, will assist the vendor in their understanding of what is needed. This then reduces pressure on the vendor in managing their production and/or inventory needs.

Relationships with drug reps, and with drug companies, are semi-restricted due to “sunshine” laws. However, the practice must question if their partner drug reps bring value in terms of clear understanding of the efficacy of the drug they are representing. Is a visit to the practice the only way that information can be obtained, or are there other options? Or, is this simply a way for the staff to get a free breakfast or lunch? From a non-physician outlook, I can only assume that it still is critical to stay on top of the latest developments in drugs.

Does your practice have an established research program? There is a clear need to partner with drug companies and other sources of research projects. Auditors will visit the practice regularly, and it is important to be open with them, providing access to the documentation they require, in order to work toward a successful research program.

Medicare and payers have significant information on the practice. In fact, they may have more data and more of an understanding of the practice in terms of patient management than you do!

The Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS), payer Star programs, and core quality measure these data through separate programs and are excellent. HEDIS is designed to help payers and their programs, meeting five domains of care. They are not measuring what the payer does, but what the provider does for the payer–patient population. The Star programs are for payers as well. The more physicians understand, and the more the payers and physicians work together, the stronger the network will be. Would the patient like to belong to a network that gets three stars out of five? The need to understand and work together with payers is critical for the success of the practice. Think in terms of federal government programs, from PQRS to MACRA measure processes. Hopefully soon these data will become available and able to be used for outcomes. The key here is the need to partner with Medicare and payers. They are part of the supply chain.

In many cases, the relationship with payers is antagonistic, rather than attempting to establish mutual goals and benefits. A revisit of this focus is in order — not necessarily with all payers, but certainly with the key payers in your practice.

Diving deeper, we identify that another real benefit of partnering is the evolution and application of new ideas. We can learn a lot more from other industries. Keep an open mind; join the Chamber of Commerce or other organizations that will expose you to the ideas of others. If a partner brings an idea to the practice, it is critical to be open to reviewing it. The idea may not work, but discouraging partners from developing new ideas, or not listening when one is presented, will have a negative impact on the relationship.

Communication

Communication is key, and it is a multifaceted aspect of the supply chain. There is the sender, the message, and the receiver. How the message is sent, whether via email, in person, written, or other, is up to the sender. The method is critical to the success of the effort.

The internet is full of comments regarding communication, with the most interesting one citing a three-part breakdown, as follows(5):

55% of communication is body language;

38% of communication is tone of voice; and

7% of communication is the words that are used.

It should not be assumed that this applies only to face-to-face efforts. Consider the receptionist who is having a bad day and answers the phone with a gruff voice and an attitude. An unwelcome message comes across loud and clear, even when it is delivered over the phone. Or the email that comes in ALL CAPS! If we are to communicate effectively, awareness of these three aspects is critical in all forms of communication.

So, how do we make communication work? Follow these steps:

Identify your partners, specifically those who are in the supply chain.

Remember that there may be a direct line, e.g., payer and practice. But there also may be others in the chain, such as the hospital, the vendor, the patient, and other providers who will assist in the care delivery

Arrange a meeting, or meetings, to work to reach agreement on expectations.

This does not necessarily need to be with all, but start with the most immediate contact and work from there

Establish mutual goals

Develop an action plan for each party, and for the joint effort:

Identify action items;

Establish priorities and milestones;

Agree on timelines; and

Assign and accept responsibility.

Develop agreement to formalize all efforts:

Establish rules of the process and;

Formalize action plans.

Regularly review progress:

Establish a regular time frame to meet; and

Be open and honest about the benefits or issues.

Revise process and agreement as necessary:

If agreed to continue, revisions may be necessary;

Implement changes;

Revise the agreement; and

Agree on the next review period.

This framework applies to any and all efforts related to the supply chain partnership.

Excerpted from The High-Performing Medical Practice: Workflow, Practice Finances, and Patient-Centric Care (American Association for Physician Leadership, 2019).

References

What is Physician Engagement? Evariant. www.evariant.com/faq/what-is-physician-engagement . Accessed December 1, 2018.

Wilson DT. An integrated model of buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science. 1995;23:335-345.

http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/trust . Accessed December 1, 2018

Supply Chain Digital. 4 Keys to Successful Supply Chain Implementation. June 2, 2015. https://scm-institute.org/relationship-based-business-model/partnerships-in-the-supply-chain/ . Accessed December 1, 2018.

Thompson J. Is nonverbal communication a numbers game? Psychology Today. September 30, 2011. www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/beyond-words/201109/is-nonverbal-communication-numbers-game . Accessed December 1, 2018.